After reading the recent NYTimes article highlighting Eddie Feibusch’s zipper business in New York’s Lower East Side, I was reminded of — what else? — the history of the not-so-humble zipper. This now-ubiquitous device that fastens and unfastens our pants, dresses, and bags, is a relatively recent invention, as far as the history of fashion goes, and also had more trouble taking off than you might imagine.

Elias Howe (inventor of the sewing machine) patented an “automatic, continuous clothing closure†in 1851, and Whitcomb Judson and Lewis Walker marketed the “Clasp Locker” in 1893, which was presented but largely ignored at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair:

It wasn’t until Gideon Sundback increased the number of teeth per inch, joined and separated them with a slider, and built a machine to manufacture continuous chains of the “separable fastener†(patented in 1917), that the zip started to take off. One of its first big customers was the US Army which applied time-saving separable fasteners to the clothing and gear of the troops of World War I. This was not, however, widely adopted by the general public.

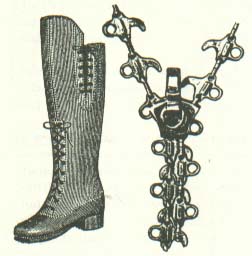

It was next incorporated into B. F. Goodrich’s 1925 rubber “Zipper Boots” (named for the “zip” sound they made), but it still struggled with mass marketing. In the 1930s a sales campaign suggested that buttons were hard for children to manage and the zipper made it easier for them to dress themselves. Using modern-day infomercial creativity, the zipper industry alerted people to problems they didn’t know they had — namely “gaposis,” gaping holes between ill-fitting buttons and clasps that exposed drafts and prying eyes to the body underneath. The solution? Spray on hair! — I mean, zippers! Exciting yes, but reliable? Not entirely. A certain amount of trial and excruciating error was enough to dissuade tailors from suggesting their clients adopt the zip (think There’s Something About Mary bathroom scene).

A well-appointed proponent of the zipper assisted its limping acceptance. The Duke of Windsor (1894 – 1972), in addition to abdicating this throne in favor of marrying the trollop — I mean divorcée — Mrs. Wallis Simpson, made a(nother) scandal by advertising his adoption of trouser flies. Known for his daring but impeccable fashion taste (mixing patterns, cuffing pants, etc.), his vocal adoption of the zip fly did much for the device. (For more on the Duke’s influence on fashion see this article.) I like the following picture of him because, though I imagine he is not actually lifting his jacket for us to inspect his fly, I like to pretend he is:

Most fashion designers only began to see the myriad of possibilities after after the zipper beat the button in the amusing “Battle of the Fly†in 1937 (I imagine an Iron Chef-like competition, though I could be wrong); Esquire magazine concluded the “new” zippered fly would end “the possibility of unintentional and embarrassing disarray,†tapping into that somewhat imagined “gaposis” crisis of the ’20s. Conservative tailors who disdained zipper flies as vulgar but who couldn’t argue with its ultimate popularity created a fold of cloth to conceal the zipper, which is, of course, the standard in flies today.

But to backtrack just a titch, the biggest breakthrough came when Hoboken zipper factories amped up the erotic associations of the zipper, capitalizing on the alluring promise of “a quick and effortless disrobing.” It was the very vulgar, potentially lewd quality of the zipper that tailors resisted but that the public loved. Synchronized dance musical director extraordinaire Busby Berkeley (1895 – 1976) tapped into the suggestive and tantalizingly promiscuous possibilities of the zipper by featuring one made of women (it didn’t hurt that they were all scantily clothed and splashing about in water). Here is “By a Waterfall” from Footlight Parade (1933) (fast forward to 3:35 – 4:18):

A whole seduction is played out with the zipper: a triangular pubis is formed by the bodies, which dissolves into the neat formation of a closed, modest zipper which a lone swimmer (the seducer) voyeuristically observes (like watching a woman dress). The zip is then ripped open by this peeping Tom who somewhat violently breaks the links. An attempt to stave off the sexual advance and reclaim self-decency is made by immediately re-zipping the zipper, and the vignette is concluded ambiguously with an underwater shot of an orgiastic flurry of confused legs and feet and not-unhappy faces. I realize this might seem like a bit of stretch in this day and age of explicit sexual scenes, but the erotic message was not lost on 1930’s audiences. I love that Busby B.!

Elsa Schiaparelli (1890–1973) was the first couturier to feature zippers as a style element. She first used brightly colored zippers on sportswear in 1930, and her 1935 collection of evening dresses were dripping in colored, oversized, decorative and nonfunctional zippers. While other designers were using zippers simply as a fastener (and trying to hide them), Schiaparelli was using them to create visual interest in garments (and maybe a little scandal too). This dress has a prominently displayed front-of-torso zipper closure that is functional and artistic, and gives the witty, Surrealist suggestion that the dress is being worn backwards:

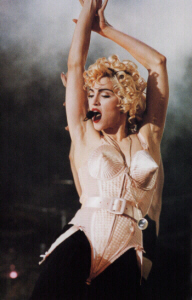

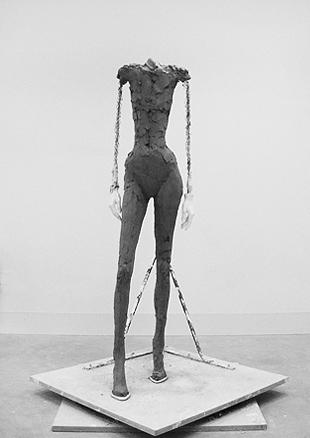

Since Elsa, other designers have used the zipper as adornment. The corset onesie Jean-Paul Gaultier designed for Madonna’s 1990 “Blond Ambition” tour had a zipper running from breasts to crotch, merging the fetish aspects of pre-20th century underwear with that of modern-day ease of disrobing:

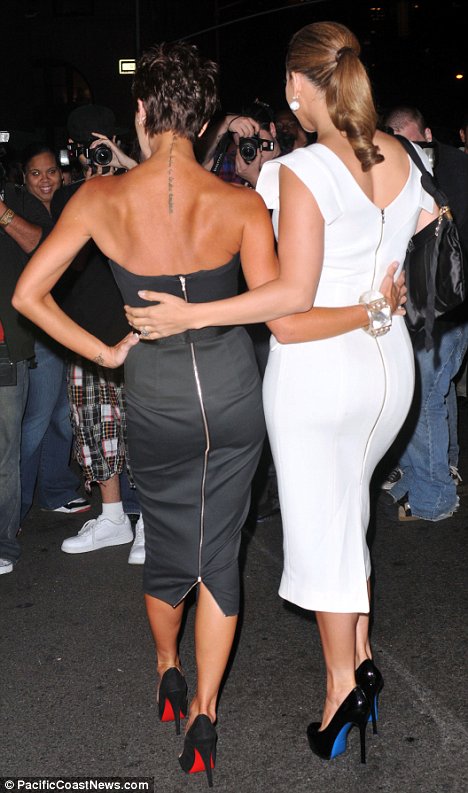

And Victoria Beckham’s fledgling fashion line often features deliberately visible zippers. Below Ms. Beckham and Jennifer Lopez are modeling former Posh Spice’s own line, with modest hemlines but body hugging silhouettes and partially un-zipped full-length zippers, hinting at impropriety without actually showing a lot of flesh:

While visible zippers lend an air of daring sexual prowess and vulnerability, so do invisible zippers that allow modern women to don boots that have 15 inches of prominent but superficial decorative lacings that fetishize the corset lacing while utilizing the practicality of the zipper:

After the initial slow adoption of the gadget, the zipper has even infiltrated our civilian vocabulary now: to “unzip” is literally to open, but also to reveal a truth, as the zipper reveals the body underneath. The hilaaaarious 1995 documentary about manic designer Isaac Mizrahi is aptly called “Unzipped,” playfully using the clasp’s undoing action to imply that the normally hidden, backstage part of the design process will be exposed. (Is it ever!)

Finally, though the zipper has come so very far from its humble origin and initial ineffectual marketing, to now being the current standard in clasps more than the exception, there remains an un-solvable problem. Easy and quick as the zipper is to close, it is equally easy to forget:

Suggested Reading:

- “Zipper: An Exploration in Novelty” by Robert Friedel

3 comments

Lexx says:

Aug 20, 2010

Great article and an enjoyable read. I’d like to add an important milestone in the fetishization of the zipper, though: The Rolling Stones’ album cover “Sticky Fingers” featuring a pair of jeans complete with real zipper. I think it was Warhol’s concept; was that the first art piece featuring a real zipper, that was not an actual item of clothing?

Tove Hermanson says:

Sep 14, 2010

Indeed, that is an awesome addition to the topic, thanks for mentioning it! (And I didn’t know it came with a real zipper!)

jen fenwick says:

May 17, 2010

Verrrrrry interesting! I will never think of zippers the same way again. I’m glad Brad Pitt has the same problem I do. Maybe it’s because we’re both from Missouri.