Steal this Style: Yippies and Political Fashions!

by Tove Hermanson on Oct 11, 2011 • 8:05 pm 3 Comments

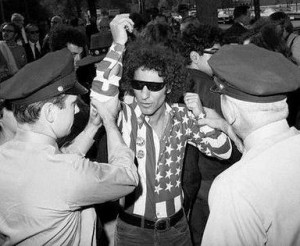

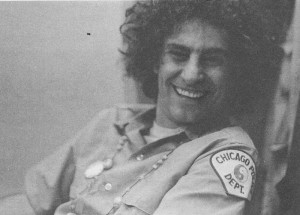

Abbie Hoffman arrested in flag shirt: “I only regret that I have but one shirt to give for my country.†October 1968

I assume readers will agree that apparel can be a powerful tool of political and social dissent, such as the Communist / anarchistic subtext of Surreal fashions (see my earlier post). Costume has likewise been leveraged in political upheavals many times; for example Caroline Weber recently illuminated fashion politics in the 18th century with her tremendous What Marie Antoinette Wore to the Revolution. I’ll concentrate on the antics of the Yippies in the 1960s.

Often indistinguishable from the less political hippies, the yippies (so-named to mimic an exuberant exclamation; afterwards the acronym Youth International Party was assigned) also cherished their long hair and thrifted clothes as protests in-and-of themselves against their buttoned-up, conservative parents and contemporaries. This is beautifully illustrated by Hair the Musical. The cast tries to explain to the authority figures, the “straights,” why they keep their hair long — is it a homosexual thing, or what? Though the lyrics leave this question largely unanswered, around 2:17 of the film clip below (1979– on the cusp of another big hair decade), the tune temporarily mimics the Star Spangled Banner, explicitly presenting hair as a political statement: “Oh say can you see… my eyes? If you can then my hair’s too short!”

Though the hippie culture was amply documented, it was still a subculture — specifically, a youth culture. In his seminal work Do it!: Scenarios of the Revolution, Yippie co-founder Jerry Rubin has a chapter “Don’t Trust Anyone Over 40,” the thinking that with few exceptions, people over 40 are too entangled in the economic systems rigged to favor the wealthy, and too enmeshed / invested in their achieved middle class quality of life to reject it. Often accused of being Communists, the Yippies actually favored communal but somewhat anarchic societies where people governed themselves. In Steal This Book, Abbie Hoffman devotes much page space to methods of obtaining goods and services for free, some of which were legal (clothes swaps, etc.), and some of which were technically illegal (stealing outright, deception). He justified the illegal methods because the Yippies believed in free necessities like food, clothes, shelter, information, and even entertainment. Woodstock (August, 1969) was a perfect example of a successful peaceful temporary community where people exchanged goods and services without money. When you consider the size of the crowd — 500,000 for 3 1/2 days — the absence of rioting and violence in favor of cooperation and generosity. There was a combination of colorful, flowing clothes, and nudity, satisfying psychedelic and au naturel aesthetics.

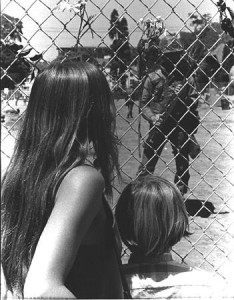

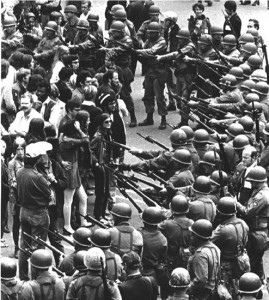

Outside special events or “happenings” like Woodstock, college campuses were hotbeds of hippie and Yippie protest activity. Yippies rejected institutional and commercialized learning (education should be free), and record numbers of students dropped out as they became disillusioned with the corporate management of their educations, preparing them not to be critical thinkers so much as model employees in the assumed next step of getting jobs, striving for management positions, jockeying for increased salaries, buying homes, etc., etc. The “straights,” terrified of the crazy-looking homegrown insurgents, treated student protests like another Vietnam: by sending in troops.

This was exemplified in the People’s Park, an unused plot of Berkeley-owned land (appropriated by totally sketchy eminent domain, evicting residents to do so) that students and non-students turned into a communal park — with 100% donated materials, food, and volunteer labor — in 1969. In effect, they re-claimed the land in a reverse eminent domain. The University retaliated after several months by fencing the park off and ultimately leveling it. When outraged students and community members tried to storm the park to reclaim it, tear gas and even bullets were used by the Berkeley and university police. Though this could be considered guerrilla warfare, it is startling how obviously unarmed the hippies and yippies are in this military confrontation:

The more draconian the police beatings, macings, and shootings were, the more outraged moderate young people became, so that Jerry Rubin actually thanked police and extremist right-wingers for galvanizing and mobilizing would-be fence-sitters for the Left.

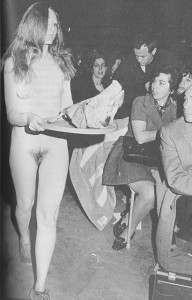

As rag-tag clothes and unkempt hair were essential to the lifestyle of hippies and Yippies, so was nudity. A symbol of the natural body, unencumbered by material possessions, it was also a form of rebellion against the repressive sexual politics of the 1950s. Yippies sometimes used the naked body as part of a spectacle, an extra “fuck you” to the uptight straights. From Jerry Rubin’s Do It!:

“[Sharon and Robin] dressed as waiters at a big feast of liberal senators at the Hilton…. Expecting their dessert of apple pie and coffee, instead were served pigs’ heads on platters. Then Robin and Sharon stripped and stood radiantly naked before the thousands of middle-class people. Horrified women hid their eyes. Men giggled and stared. Shelly Winters threw her cocktail at them. Some women began beating naked Crazie Sharon’s beautiful thighs with umbrellas….”

I mean, just look at the absolute disgust and horror of those onlookers! Though public nudity has once again subsided into designated spaces, one has to wonder why the naked body is so offensive to so many.

To backtrack a bit, the Yippies were founded by adopted New Yorkers Abbie Hoffman (1936-1989) and Jerry Rubin (1938-1994), among others, in 1967, an offshoot of the less radical hippies. They set out to garner as much media attention as possible to their disappointment with America’s foreign agenda and domestic capitalist system. After organizing a protest rally of the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago — it was a protest of the entire electoral process, not any specific candidate or party — the Chicago police, acting under Mayor Daley‘s draconian orders, engaged in drawn-out warfare with peaceful rally-goers, employing tear gas, baton beatings, barbed wired jeeps, and large guns. Though Time Magazine noted, “Not so innocently, many [protesters] were equipped with motorcycle crash helmets, gas masks,… bail money and anti-Mace unguents,” these were protective measures, not offensive weapons, and were a direct result of the threat of violence from the oppressive mayor who denied many protest permits and gave “shoot to kill” commands at previous student protests. Furthermore, most protesters were armed with nothing but signs and flowers.

After disrupting the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, eight token protesters (Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, David Dellinger, Tom Hayden, Rennie Davis, John Froines, Lee Weiner, and Black Panther Bobby Seale) were arrested and tried for conspiracy and inciting to riot. During the kangaroo court trial of these “Chicago Eight,” Abbie and Jerry used costume to humorously — and effectively — illustrate their discontentment with the American government and court system. After enduring an outrageous miscarriage of justice under Judge Julius Hoffman, Abbie and Jerry started rebelling even more aggressively than their normal unbathed and long-haired selves: they came to court one day wearing judge’s robes, and underneath were Chicago Police uniforms, mocking the kangaroo court they were forced to participate in (“Our attitude is basically satirical,” said Yippie Keith Lampe). Look at Abbie’s impish grin in the costume of a Chicago Policeman — his wild hair and beaded necklace identifying him with his subculture in the midst of the joke — even while in the midst of a rather serious trial where fellow defendant Bobby Seale was literally bound and gagged:

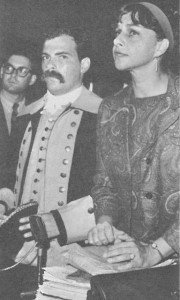

And In front of the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), Jerry Rubin dressed as a Viet Kong solider, and as an American Civil War soldier while handing out copies of the Declaration of Independence:

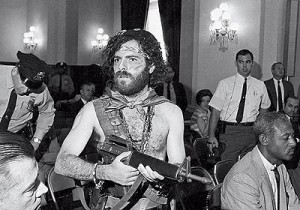

To other HUAC hearings (he was investigated twice), Jerry tried to dress as Santa Claus (“to reach the head of every child in the countryâ€), but was barred from defaming the Christian idol. He was, however, allowed to wear a full-on guerrilla warfare costume (toy machine gun included!), which he did multiple times, dressing as the revolutionary outcast he felt himself to be:

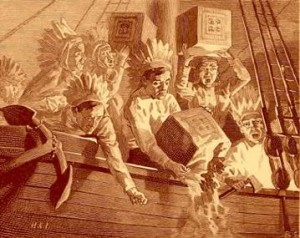

More than stoned theatrics, farcical costume was deliberately employed to attract mass-media attention to the Yippies’ anti-war, free-speech, anti-corporate agenda. But where did the Yippies get their inspiration? The Boston Tea Party was an early American event where costume was used for political purposes. The Boston colonists rebelled against their controlling motherland England, and the conspired monopoly of the East India Company. In December, 1773, Boston colonists, dressed as Native Americans, boarded three taxed tea ships and threw the goods overboard, as protest against taxation without representation. Costume was critical for multiple reasons: first, it created a spectacle that demanded attention; but though the outfits garnered interest to the group event, they also disguised the individuals from identification in an act of vandalism.

Traces of the Yippies can then be seen in the historical costumes of the contemporary costumed Tea Partiers too, obviously from the opposite end of the political spectrum. The Yippies’ desired “free market” — literally free essential services — is twisted into the Tea Party’s desired “free [corporate] market”:

And though the costumed element is not as consistent thus far, Occupy Wall Street shares a great deal with the Yippies. It too has a nebulous but anti-corporateagenda, there is general anti-war sentiment, and there are a few people dressing up to illustrate their points. Zombies are being equated with blood-sucking corporations and bankers, and some veterans are donning Guy Fawkes masks, a symbol of the Anonymous group that started OWS:

While anger over injustices was most certainly a prime component of the Yippie movement, humor was the preferred method of communication. Abbie Hoffman specified: “The YIP is a party — like the last word says — not a political movement.” While localized rallies and sit-ins and happenings and marches are important, life itself should be a living theatre of protest. Costumes, perhaps, have a place in the former, while clothes with a conscientious message can be used every day to express one’s participation (or non-participation) in ingrained systems (see my previous post on Collecting Clothes with a Conscience). Politicize your clothes!

And if you’d like to hear more, I’ll be elaborating on this topic this at 10.45am on Friday (October 14) for Fordham’s (free!) “The Art of Outrage” conference in New York’s Lincoln Center. If you have Friday off, come on down!

3 comments

Chris young says:

Mar 18, 2016

This is one of my favorite iconic images of the 60’s revolution ,my version from my copy of Do It by Reubin.Its still true today-the server represents the post war generation and culture -SANDERS 2016 REVOLUTION!Chris Young

Tove Hermanson says:

Jun 4, 2013

Thank you, Bob, for sharing, and reminding us that the political schemes are less of a linear spectrum and more of a loop, with inevitable intersecting interests. That said, it often seems that Yippie’s brand of anarchism / communism is at odds with Tea Partier’s Christianity-driven moral policies.

Bob says:

Jun 3, 2013

I was a supporter of the Chicago 8 (and protested on campus) and I also gathered with Tea Partiers on the Washington Mall. My political views have changed very little over that time so I don’t quite get the “obviously from the opposite end of the political spectrum” quote. I was and still am protesting for the right to conduct speech, love and living outside of the suffocating paternalism of the establishment.

Bob in Portlandia (where the feds have just ordered us to spend $200M to cover our water reservoirs, despite supplying the cleanest drinking water in the nation).