Symposium Recap: Authenticity in Yale’s “Urban Catwalk”

by Tove Hermanson on Apr 26, 2011 • 2:03 pm 2 CommentsIt was excitement and ultimate delight that I attended (and presented at) Yale’s “The Urban Catwalk” conference this past weekend. Though ostensibly the theme was street fashion, as with most conferences, this topic was expounded upon by a wide range of scholars from vastly different fields (performance studies, French history, literature, communications, etc.). More even than “street” or even “public space,” the concepts of “authenticity” and “identity” surfaced again and again in these lectures, and interestingly with vastly different implications.

April Calahan spoke about the French penchant for increasingly towering, sculptural hats during the WWII German occupation. While strict rationing of traditional fabric and leather limited fashions at first, soon tailors and cobblers began experimenting with non-traditional materials like cardboard, ribbons, fake food, etc. to create increasingly flamboyant and odd accessories. With gasoline shortages, bicycle culture rose steeply and clothes that facilitated athletic movement gained popularity, but as clothes became more practical, hats became less so. Though she focused on a large group– the French– Calahan emphasized that the often bizarre, towering hats of this period silently but obviously defied the Germans with a quintessential French industry– flamboyant fashion– to assert French collective identity against oppressive invaders.

Along similar lines of collective opposition, Jessica Metcalfe gave a fascinating talk about Native American resistance in contemporary streetwear. She pointed to the 19th century assimilation efforts of placing of Native American children in English/American-style boarding schools and that those children were ritualistically stripped of their native clothes and re-dressed in Western styles. (This very much reminded me of Marie Antoinette’s ritual stripping of her Austrian clothes and re-dressing in her adopted French styles.) Metcalfe showed many examples of current, young Native American graphic artists who screenprint familiar Native American motifs (blankets designs, Sitting Bull, buffalo) on modern Western clothes items (hoodies and T-shirts) as Native American activism. Christopher Columbus and 1492 are recurring references (“Fuck Christopher Columbus”) as a key moment of the marginalization of Native Americans. Metcalfe pointed out that there are many tribes all over America, but Native American activist organizations have consciously appropriated pan-Native American motifs, counting on their generic recognizable symbolism to communicate. For example, a feathered headdress– which is only actually worn by chiefs in the plains– to symbolize Native American strength, power, and a position of authority. This kind of “authentic” protest is especially important as Hipsters and stylists adopt sexified trendy Native American styles like fringed moccasins, “Navajo” print jackets, and headdresses.

Several people discussed the relationship between hip hop music, fashion, culture and black identity, and though I think this is a rich course of study, I also think it’s difficult to say anything new about it. Matthew D. Morrison spoke about sagging pants and the so-called relationship to criminality; this reminded several audience members (and me) of the recent French ban of veils, and I wished Morrison had spent a little more time dissecting how / why government attempts to combat cultural blight like criminal violence, oppressive misogyny, etc., by banning clothes associated as the result (or perhaps the precursor?) to these injustices. (See my earlier post on Innerwear as Outerwear.)

Siobhan Carter-David cataloged every Essence Magazine in the ’80s and early ’90s and made the interesting discovery that though no issue in the ’80s ever championed or even portrayed urban black style (layered doorknocker earrings, for example), in the ’90s they did retrospectives on the importance of hip hop fashions. Very interesting that showed how even the black community has been slow to acknowledge hip hop as a relevant style worthy of emulation (this reticence speaks to the strength of associations between hip hop fashion and urban criminality or other undesirable qualities).

In spite of my general boredom of things relating to hipsters, Heidi Khaled linked modern-day hipsters to their historical counterparts. From bohemian artists of the 19th century to the beatniks (apparently formerly known as “hipsters”), to the “hippies” of the ’70s, she traced the lingering associations between these arty types and elite liberalism, to the contemporary concept of consuming cool in today’s hipsters. By pointing out the fine line between earlier artists who were caught between the desire to create “authentic” art and the need to please their patrons, she indicates a puzzling disconnect between today’s aspiring artsy hipsters and true individualistic “authenticity.”

Though he was not the only Performance Studies scholar, Kalle Westerling was the only presenter who incorporated performance into his discussion of performance, which I appreciated conceptually and thoroughly enjoyed. He opened by enacting a kind of poem, enunciating click sounds of lipstick and glosses and glitter as he applied the products to his lips, just before running this video in its entirety:

First: I want Erickatoure’s first ensemble for my own. Second, I loved the connection between Westerling’s lipstick clicks to the shoe clicks used as percussion in the video. He went on to discuss the intimate relationship between drag queens and their clothes– their shoes especially– in forming their identities which are sometimes separated from their drag characters and sometimes not. Performance pervades this relationship, whether on a stage or on a sidewalk.

Daphne Carrpresented part of her book on Hot Topic stores and the irony of the existence of a serialized box-store that caters to supposed sub-cultures like Goth, Emo, Grindcore, etc. She has done exhaustive research on the Hot Topic store chain and it’s even more contradictory off-shot C28, the Evangelical Christian spin-off that uses the same “alternative” aesthetic in store decor and merchandise to sell Christian paraphernalia. What does it mean when “alternative,” “individualistic” visuals become corporate and even conservative religious, and why don’t consumers seem to find this contradiction problematic?

Both Lauren Walsh and Pia Sahni spoke about the non-existence or exoticization of ethnic minorities, especially Indians. Though I certainly agree that there is undoubtedly pervasive white-ness to fashion spreads and fashion runways, and a simultaneous fetishization of those excluded “exotic” people, Walsh and Sahni used the word “authentic” to indicate there was a lack of authenticity in these slanted shows and ads– as though an “authentic” advertisement is possible or exists somewhere else.

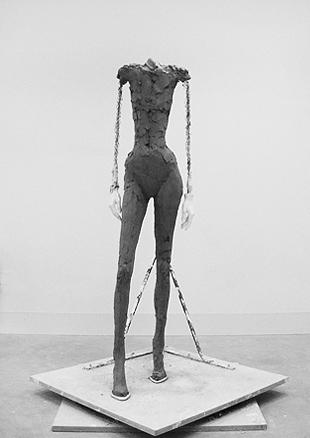

Keynote speak Caroline Weber (author of the outstanding book What Marie Antoinette Wore to the Revolution) also touched upon “authenticity” and “identity.” In her history of the dress form and mannequin, or “Pandora,” in Paris, she said a major downfall of Marie Antoinette was that she allowed a lifelike, life-size mannequin of herself to be created, to be dressed in her fashions and shipping all over Europe. Though ostensibly used to disseminate the queen’s style for imitation, the inanimate mannequin was greeted by cheering crowds who treated it as a stand-in for the queen herself. While charming, this nonetheless conditioned people to view the mannequin as a live person, and conversely to view the live queen as an inanimate thing to the point that, when the French Revolution rolled around, she had already been literally dehumanized and it wasn’t so shocking to dismember / behead her. In fact, part of the outrage the French people directed at the throne was due to Antoinette’s mannequin, which they now claimed sexualized and debased their monarchy by allowing commoner’s hands to paw the likeness of the queen. The royal authenticity of the queen had been questioned after her mannequin double was accepted as her; I imagine allowing copies of her royal wardrobe was a similar offense as revolution rumbled, even though the same people had clamored for those very knock-offs.

Not so very much has changed in subsequent centuries: don’t we love the supposed originality of new design collections, don’t we crave affordable knock-offs immediately, and then don’t we discard them when they are so affordable they’re pervasive and we no longer appear “individual” or “authentic?” My question is, does authenticity exist at all?

2 comments

Tove Hermanson says:

May 24, 2011

Thanks for commenting, Anita. There were certainly more nuances to all presentations than I was able (or perhaps willing) to elaborate on, but I willingly concede that Sahni’s use of “authenticity” as it applied to the Native American culture was quite complex. I suppose I too was interested in the conflicting, or at least concurrent, uses of “authenticity” within the conference as a whole, and so gave short-shrift to each presenter’s self-contained exploration of this topic (Sahni’s was one of the best, in my opinion, and I did not mean to imply that her lecture was one-sided in this regard.)

Anita says:

May 2, 2011

Thanks for sharing this. One of my former students presented at this and the representation of her argument does not seem to be quite right. Sahni has a lot more nuance to her thought and I just have to speak up in defense of her awesomeness and ability to critique discourses of ‘authenticity.’ 🙂 I don’t think her work is about reifying a kind of authenticity as much as it is about critiquing the desire for a kind of authenticity that emerges in different discourses. I’ve read her work closely and she is more interested in questions about why the ‘authentic’ carries cultural capital even a kind of fetishistic desire for it and where the line between appropriation and desiring some kind of fabled idea of the authentic comes into play.