I read with some interest the Times article Obama Says Forum’s Costume Photo Is Unnecessary. This refers to the tradition of the 21 members of the annual APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation) forum participating in what has unfortunately been dubbed “the silly shirts photo.” Past photo-ops “have included ponchos and what looked like gowns for pregnant bridesmaids,” Jackie Calmes wrote. Frankly, I’m surprised by Calmes’ snarkiness.

At the first meeting in Seattle in 1993, then-President Bill Clinton outfitted the leaders in leather bombardier flight jackets. This fun photo-op idea subsequently became a tradition to don the national dress of APEC’s revolving host country; leaders wore the outfits for the photo and the rest of the day. Let’s take a look at past ensembles and judge for ourselves, shall we?

1994 Indonesia, Batik shirts

Batik is a wax-dying technique that, in certain regions, can takes inspiration from everyday life like flowers, people, Arabic calligraphy, European bouquets, Chinese phoenixes, or Indian peacocks, marvelously illustrating the influences upon Indonesia as a land. There are many batiks specific to momentus occasions (weddings, funerals, births), and batik is often an integrated part of such ceremonies. During an expectant first pregnancy, mother-to-be is wrapped in seven layers of batik while being wished well (“naloni mitoni”); and batik is incorporated into another ritual when a baby touches the earth for the first time (I just like the very existence of such a ceremony!). Though I don’t have expertise enough to name the batik prints worn by esteemed APEC leaders below, it is easy to see the variety, and fun to imagine the rich history that produced such “classic” motifs.

1995 Japan (Business suits)

It was decided that the familiar kimono was too restrictive to be worn comfortably by APEC members, so they all wore suits. Not only disappointing, this excuse is curious to me, as Samurai wore kimonos and had notoriously physically active lifestyles.

1996 Philippines (Barong shirts)

Barongs are very lightweight and white (speaking to the climate of the Philippines), common formal attire for men and sometimes women. The barong was popularized by Ramon Magsaysay when he wore it to his inauguration as president in 1950, and most formal affairs afterwards (reminds me of Josephine popularizing the “Empire” gown at Napoleon’s coronation.) Dubious legend has it that the invading Spaniards forced Filipinos to wear their barongs untucked (Spaniards would wear them tucked) for easy class distinction, and they allegedly took advantage of the barong’s translucency to see if Filipinos were attempting to conceal weapons. Accurate or not, it’s telling that these possible myths about the national garb being used to control the native people endure.

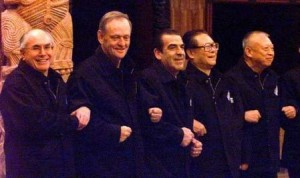

1997 Canada (Leather jackets)

I must admit, bomber jackets don’t really scream “Canada” to me, but feel free to offer hypotheses of relevant history!

1998 Malaysia (Batik shirts)

Though a similar wax-removal dying technique is used in Malaysia as in Indonesia, there are some major differences. First, depictions of humans or animals are rare because such images for decoration are forbidden in Islam (the butterfly is an exception, for some reason). Malaysian batiks are highly vivid, unlike the earthy Indonesian tones. The Malaysian government has been heavily promoting the adoption of batik as a national outfit, even encouraging civil servants wear it on the 1st and 15th of every month.

1999 New Zealand (Sailing jackets)

As an island New Zealand clearly has an oceanic ties, solidified far before the British colonialists arrived by the indigenous and ingenious Maori. When I myself sailed there in 1997 as a high school student aboard the now sunk (!!) Concordia, New Zealand had just won back the America’s Cup sailing prize, and goddamn, the whole country was abuzz with pride. I enjoy the outdoorsy look the weatherproof jackets give the dignitaries, though I’m disappointed they obliterate any reference to the native peoples who sailed around the island first.

2000 Brunei Darussalam (Kain Tenunan shirts)

Southeast Asia has developed its textiles over centuries (the earliest recorded mention of cloth-weaving in Brunei Darussalam can be traced to the turn of the 16th century), and motifs include leaves, local flowers, and Islamic patterns. A sad consequence of modernism has been a drop-off in interest in this labor-intensive art. Since 1975, the Brunei Arts and Handicrafts Training Centre (BAHTC) has been apprenticing small batches of trainees in traditional handicrafts such as weaving, but it might be relegated to a curiosity in the not-too-distant future. I wish I could better see the embroidery on the APEC shirts to discern a pattern or significance.

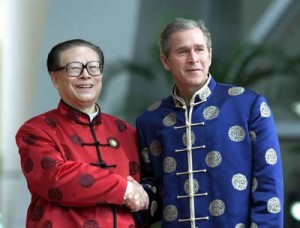

2001 People’s Republic of China (Tangzhuang shirts)

The Tangzhuang is a jacket that originated at the end of the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), modified from the Manchu clothing Magua. Typical colors are red, dark blue, gold and black, and Chinese monograms with good wishes are a common motif (lovely sentiment, right?). Initially it was only worn by the elite classes, though it has trickled down to be worn by all in modern times (even women, if you can believe it!).

2002 Mexico (Guayabera shirts for men/HuipÃles for women)

The origins of the Guayabera shirt is actually hotly contested — most Latin American countries, Cuba (which declared it its national garment in 2010), and even the Philippines claim it as their invention. There is a Cuban legend that a poor seamstress sewed large pockets on her farmer husband’s shirt so he could carry guavas home. Guayabera shirts are traditionally white or very pale, with 2 -4 large pockets, side slits, and vertical rows of tiny pleats. They’re worn for special and casual occasions all over the Caribbean. A huipil is a tunic / blouse worn by the indigenous women of Mexico, Central America, and northern South America (and by men in Guatemala). The elaborate decorative embroidery may convey the wearer’s village, marital status, and personal beliefs. (I wish we could see more detail in the APEC photo.)

APEC in Mexico, 2002

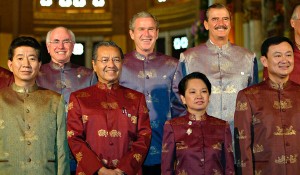

2003 Thailand (Brocade shirts for men/Brocade shawls for women)

Richly embroidered brocade — material with raised texture — is the most expensive type of silk and was only worn during ceremonial occasions like weddings. This clearly speaks to the natural resources (mulberry trees, food of silk worms) and accompanying silk industry, to say nothing of the Silk Road relationships. To even untangle silk from woven cocoon to useable thread is an absurdly time and labor intensive process, and silk has always been a luxury fabric, worn by the royal court, favored by the Prime Minister’s wife, and often given to visiting dignitaries. Ironically it was an American — Jim Thompson — who revitalized Thailand’s declining silk industry in the 1950s and ’60s.

2004 Chile (Chamantos)

Similar to a poncho (but apparently not exactly the same), chamantos are decorative garments from central Chili woven from silk and wool, with ribbon edging. Each side of a chamanto is fully finished, and one side is lighter colored than the other for variety; the dark side is typically worn during the day (perhaps when it would absorb the most of the sun’s rays in the chilly mountains). Common motifs depict local flora and fauna such as copihues —Chile’s national flower— and various birds.

2005 Republic of Korea (Hanboks)

Hanboks, colorful, pocket-less garments with sleek lines, are the traditional costume of Korea; it literally translates as “Korean clothing.” Though historically commoners wore hanbok and rulers and aristocrats wore more foreign-influenced designs, they have always been worn ceremonially. Hanboks were designed to facilitate ease of movement and also incorporated many shamanistic motifs, indicative of their nomadic northern Asian origins.

2006 Vietnam (Ão dà i)

As opposed to the A-line looseness of the hanbok, the áo dà i is a closer fitting silk tunic worn over pantaloons. Originally an 18th century court dress, over centuries it evolved. In the 1920s and ’30s, artists modernized it as a female dress, and in the 1950s the waist was tightened to produce today’s silhouette (men’s fit is still un-cinched). Typically a female dress, the áo dà i is imbued with feminine and nationalistic symbolism (interesting, given the unfortunately typical male-dominated politicians in APEC).

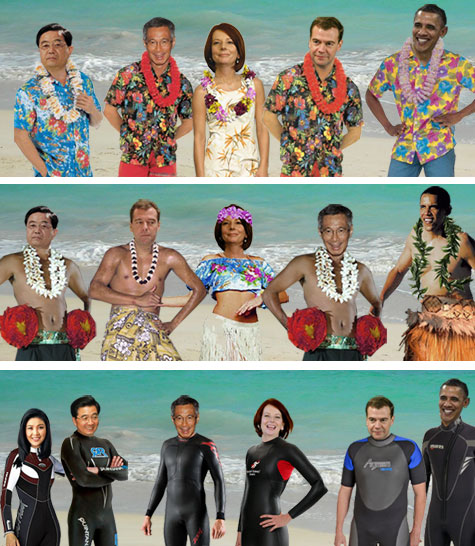

2007 Australia (Driza-Bones and Akubra Hats)

“Driza-Bone” (“dry as a bone”) is an Australian company specializing in foul weather gear, established in 1898 by a Scottish immigrant. Initially developed to protect horse riders from the rain, they were originally made of oiled sail boat sails. With some irony, the company moved back from an extended international hiatus to Australia a year after APEC gathered; but perhaps the “silly photo” garnered enough attention to spur the return? Unfortunately this photo doesn’t show the akubra hats, but they’re the typical wide-brimmed hats of the Australian bushmen, not dissimilar from functional American cowboy hats which protected the wearer from harsh wind and sun.

2008 Peru (Ponchos)

Protective woolen ponchos have been worn by the peoples of the Andes since pre-Hispanic times. A gorgeously simple and un-wasteful design, they are constructed from a single square of woven fabric with a center hole cutout for the head; waterproof versions may have fasteners to close holes and hoods to protect from heavy weather. Though this is inevitably one of the APEC outfits that’s the butt of many jokes, latex-coated military ponchos have been worn by Americans since the 1850s and were used in the American Civil War as a multipurpose jacket, tent, or ground-covering sheet for sleeping. They have consistently been a part of American military accoutrements ever since, albeit in technologically edgy textiles. Peru had the original!

2009 Singapore (Peranakan-inspired designer shirts)

Peranakens are the descendants of late 15th and 16th-century Chinese immigrants to Indonesia; they clung to many of their traditional ways of life such as ancestor worship, but assimilated with the culture and language of their new land. Traditional designs often incorporate Chinese symbols, and shoes often have European flowers, but depicted in local bright palettes.

2010 Japan (Smart casual)

Prime Minster Naoto Kan cops out of kimonos once again. (I’m not going to get into the history of the dark business suit at the moment, but frankly, I associate it more with English / American history than with that of the Japanese, yet in light of all the other foreign influences present in previously mentioned national costumes, it should not be so surprising that the two-piece suit has become ubiquitous for businessmen / politicians everywhere.)

2011 United States (Business suits)

I really love seeing familiar leaders in the colorful, unfamiliar dress of these countries. It makes me question (again) the prejudices the western world has against color, decoration, and unisex clothing on men — this of course taps into ideas of masculine identity and classicism. It also strikes me that from a distance, when the members are in a line in the same outfits, they look like they’re unified. They look like they’re working together. Whatever differences they may have in skin tone or hair styling or ideology fades to the background, and they appear to be a unified body. And shouldn’t they?

It was especially interesting to me that Obama chose to dissolve the tradition in his own home state, where presumably he feels the most comfortable in the local garb. Chilean President Piñera Echenique was said to have asked, disappointed, during this year’s APEC meeting, “Where are the Hawaiian shirts?†It has been speculated that Obama deemed the bright floral inappropriate for these austere economic times, but I would argue that’s exactly when color and patterns and art and fun are the most needed — to lift our spirits. I recently had a discussion with an activist friend of mine who has deliberately been toning down her wardrobe as she becomes more involved in radical organizing because she fears colors and patterns or anything “fashionable” would be considered bourgeois in her line of work. I pointed out that the most ostentatious dressers I know are typically artists — a group famous for its financial struggles and radical alliances. This may be so, my friend conceded, but within Marxist ideology, there is a long history of vilifying fashion as a non-useful and therefore frivolous waste of energy and resources. <sigh>

But to return to the topic: if the impetus for abolishing the APEC costume tradition is so-called lack of dignity or a fear of appearing foolish, I must protest on three counts. First, politicians are known to be stuffy, conservative (i.e. “boring”) dressers, and it might actually do some good for their public images (and their cause with APEC) to be seen as real people who actually get silly and have fun — like us norms. Second, and this is a greater problem in my mind, this discomfort in native dress, even for a “silly picture,” highlights the prejudices of one culture towards others. “Ponchos and batik shirts might be fine for the locals, but that ridiculous look is normalized where they live!”

Lastly, as a fashion culturalist, I emphatically believe that clothes are imbued with socio-cultural significance. When you stop to ask why the national dress of various countries, even within a relatively small geographical area, are different (and also how they overlap), you are forced to confront the histories of those countries, their natural resources (silk production of Thailand), their climates (heat of Mexico), their wealth distribution (Thai brocade silks), their political systems (Shanghai Mao collars), what kind of work and activities the populations engage in (Peruvian / Chilean ponchos facilitate movement; New Zealand and Australia’s stave off extreme wet weather). Empathize with another man by walking in his shoes? Why not pose for one so-called “silly picture” in another man’s whole outfit? I dare you to not get a new perspective on your own ethnocentricity.

1 comment

Michael says:

Mar 23, 2012

Inspiring. Playing poker this afternoon and have decided to pull out my old polyester Hawaiian shirt that I bought for $7.50 in 1995. Still looks as good as new. You can tell your Marxists friends that colors are durable. Besides, I can think of at least two radicals who were fashionable – Tom Wolff and Edward Said.