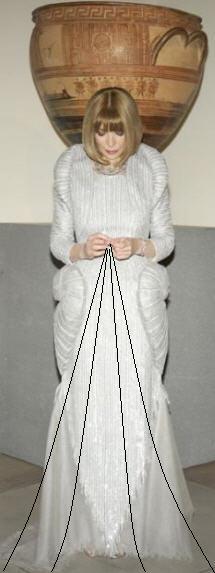

Anna Wintour’s involvement with the Metropolitan Museum is reestablished at this time every year with the Met’s renowned Costume Institute gala, and we are again bombarded with pictures of A-list celebrities, socialites and models attending the lush affair. Whether attendees are portrayed in adoring light or to ridicule their outrageous outfits, the glut of coverage across paper publications and the internet succeeds in generating widespread coverage and awareness of the event, invaluable marketing for both the Met and the gala’s loud sponsor, Vogue. These sorts of relationships are so ingrained in our capitalist system that many don’t give Anna Wintour’s involvement in this museum fundraiser a second thought but, for me, it highlights the uneasy balance between cultural institutions and their sponsors. Especially in times of economic hardship, relationships between art centers and their patrons are ever more precarious and therefore precious. Among museums the Met retains one of the most prestigious reputations in the world. But the news that is perhaps the most widely disseminated about the Met every year is not about its new acquisitions, nor its beautiful newly renovated American wing, but the Costume Institute gala, arguably the most hotly anticipated social event — to say nothing of fundraising events — of the year.

The 700 invitations are coveted by high society and pop culture icons alike, and the photos are disseminated equally by pop culture websites, blogs, and newspapers. I freely admit that I comb the internet for photos of the chic attendees — more than other galas or award ceremonies even — as there is always a fashion theme relating to the spring costume exhibit that is supposedly being promoted by the event, which I think prompts people to be even more outlandish in their sartorial selections than they might otherwise be, glamorous lives notwithstanding. This year’s “Models as Muse†was a bit weak in terms of gala inspiration (it resulted in many haute micro-mini skirt ensembles), but it did succeed in attracting celebrities who may or may not actually be personally invested in the museum’s mission (specifically the “advance knowledge of works†“in accordance with the highest professional standardsâ€), but whose presence attracts the photographers nonetheless.

Michael Gross concentrates on the questionable relationship between the Met and Vogue in his newly released book “Rogue’s Gallery: The Secret History of the Moguls and the Money that Made the Metropolitan Museum.” In it, he blames the Met’s collaboration first with Diana Vreeland and then with Anna Wintour to co-host the Costume Institute fundraiser which, he claims, has been twisted into a publicity platform for Vogue and Wintour’s personal vendettas, displacing the Met’s own mission. “The most highly publicized event at the museum has been turned into a magazine and movie-promotion party, where Anna sells herself and movie stars sell their latest projects,” said Gross. “What gets lost in the process is the museum.”

Suspicious as I am of Vogue’s motives (it is clearly in their best interest to invite the beautiful people they’d like to court to be in Vogue’s own pages), I whole heartedly support utilizing an institution’s fashion collection as a revenue generator — which the Costume Institute absolutely is for the Met, raising a significant portion of the museum’s income (the 2008 total of which was $297,790,000). First, as demonstrated by my drive to work on this very blog, I believe there is a wealth of knowledge — social, financial, and political history for starters — to be gleaned from the study of clothes, just waiting to be disseminated in an engaging and articulate manner. I crave museums tackling projects involving costume. Tragically, many institutions small and large (i.e. Merchant House, Brooklyn Museum) have fabulous costume collections that are rarely displayed and even more rarely exhibited in-house due to budget, space, staff, and/or costume history expertise shortages. Second, costume exhibits have been proven to be excellent revenue generators precisely because anything fashion related draws in younger, pop-culture obsessed people who may not otherwise attend museums that have the unfortunate reputation for housing stuffy, inaccessible “high art.†I have no problem whatsoever utilizing fashion exhibitions to tap into this market. Isn’t the goal of museums to market their exhibitions to attract in people, and then actually teach them to look more deeply into a subject they may only have had a superficial understanding of?

The trick is for museums to capitalize on this obsession with glamorous fashion. Obviously, money can and should be raised for the institutions. Museums increasingly struggle for attendees, and in this free market democracy, private investors are relied upon to fund so-called worthy projects more than the government is. With the latest financial crisis, corporate sponsors have become ever more sparse (working for the Development department of a New York museum, I have witnessed this scramble first-hand). In some cases, this has forced museums to hike their admissions (in New York it’s not uncommon for tickets to be $20), which has the unfortunate cyclical consequence of making these exhibitions even less accessible to the general public.

Do these galas confirm the perception, accurate or not, that fashion is inaccessible to the mainstream public? Or worse yet, that the study and presentation of fashion in an historical context is unimportant, has no bearing on “serious” studies, offers no insight into history, and has no greater implication on or by current events? My fear with the Met Costume Institute gala is that Vogue’s self-promotion cannibalizes what could and should be an opportunity to present fashion as an incredible marker of human civilization that varies according to technological breakthroughs in materials, social morays, etc. I’m doubtful these parties accomplish this. And this is due, in part, to the accompanying spring Costume Institute exhibitions that are usually of the blockbuster variety with a lot of flash and glitz, but weak-themed and presented with little-to-no background information drawing from a larger historical context, which in my mind must be the crux of any exhibition, costume or otherwise (I am specifically thinking of the popular but superficial “Chanel†and “Superheroes†exhibitions).

As friends know, there are few things that exasperate me more than a flubbed costume exhibit. The wasted opportunity hits me like a brick in the face: that money could be collected, venue provided, fashion displayed, and the opportunity to use costume as a teaching tool not utilized kills me. Partly because I’ll walk away disappointed for the lack of new information I personally collect, but mostly because I’m all too aware of how superfluous and flighty the majority of the population views fashion, and exhibits that don’t treat the subject academically confirm people’s belief that there is nothing but pretty, outrageous, or at best creative works at play and nothing deeper. This is perhaps a I see the Met’s Costume Institute gala as just such a wasted opportunity to broaden the public’s opinion and understanding of fashion’s relevance and importance.

Museums must weigh the pros and cons of the opportunities corporate money affords them — not just more elaborate exhibits but more advertising to reach wider audiences — versus the control corporate sponsors believe they become entitled to exert (i.e. Rudy Giuliani’s attempt to cut the Brooklyn Museum’s public funding when it exhibited controversial material in the “Sensation” exhibit of 1999). The American Museum of Natural History in New York actually had trouble securing sponsorship for their 2005 Darwin exhibition because (exasperating as it is to me), creationism and the so-called “theory” of evolution continues to be incendiary and corporations were afraid of alienating their own potential supporters, political and financial. (Ironically — or not so? — once funding was secured, the Darwin exhibition was extremely popular.) The Museum made up for this difficulty with its latest corporate partnership.

The movie series Night at the Museum prominently incorporated two Smithsonian museums: the first film (2006) took place in the Museum of Natural History, the second (2009) in the Smithsonian Institute, and it actually contains “Smithsonian†in the title: marketing jackpot! This arrangement gave writers license to incorporate actual Smithsonian-owned ephemera (like Amelia Earhart’s plane, Dorothy’s ruby slippers, etc., used to great comic effect) into the plots, and both museums have enjoyed the reciprocal reaction of an immediate and impressive surge in attendance. I see this as a fair exchange. Like the Museum of Natural History, the Met needs to reassert its power and purpose with Vogue (or another sponsor), because the Costume Institute is more than an exclusive venue, and should be leveraged as such.

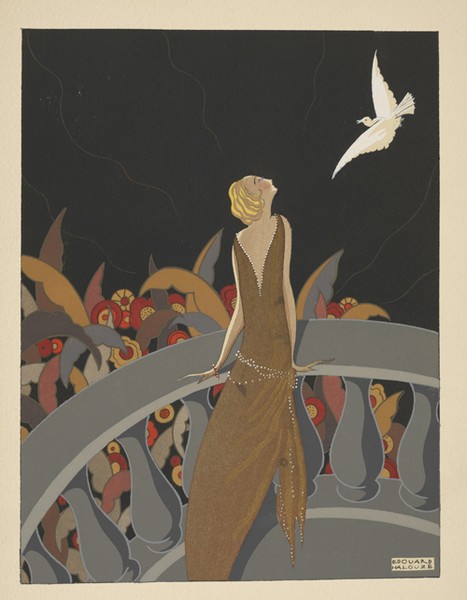

Much as I’ve concentrated on current corporate collaborations, the alliance of patron and artist (or art institution) is not a new subject, though it’s taken new forms. The Mérode Altarpice is a triptych by the early Netherlandish painter Robert Campin, c. 1425 – 1430. Though ostensibly a religious painting depicting the popular Annunciation, the commissioning family was painted directly into the religious scene (left panel). They also guaranteed their identities by their coat of arms seal in the window, and by the presence of a costume (yay costume historians!) typical of a town messenger from Mechelen, where the family was from.

As religious paintings waned in popularity, patrons continued to be inserted into works. Fragonard’s “The Swing†(1766) is a delightfully naughty painting portraying a pink-clad woman (I will refrain from dissecting her ensemble in greater juicy detail, though I’m tempted!) being pushed on a swing by a bishop in the background, while her “hidden†lover in the foreground gazes admiringly up her yawning skirt. John Fleming writes “The identity of the patron is unknown, though he was at one time thought to have been the Baron de Saint-Julien, the Receiver General of the French Clergy, which would have explained the request to include a bishop pushing the swing. This idea as well as that of having himself and his mistress portrayed was evidently dropped by the patron, whoever he may have been.†Fleming points out “the picture was depersonalized and, due to Fragonard’s extremely sensuous imagination, became a universal image of joyous, carefree sexuality,†(my italics) as opposed to a straightforward vanity portrait. Since then, corporate sponsorship has replaced less conspicuous donations as a major funding vehicle for many arts organizations.

So collaborations between moneyed patrons and starving artists has not been uncommon historically, but patrons were not advertising themselves — no revenue was expected from the inclusion of their images in commissioned paintings, unlike corporate sponsors today who slap their logos on every visible posterboard. There can be mutually beneficial relationships — partnerships — established between non-profits and corporations (as with Fragonard and his patron), but it’s vital that those non-profits remember that they need not be beggars bending to the whim of their sponsors. Corporations can offer money, but museums offer credibility in public relations and marketing return. Children today may very well associate Exxon Mobile with the funding of public television instead of my own foremost memory, the infamous Exxon oil spill of 1989, and the Altria Group, owner of cigarette giant Philip Morris, is not coincidentally one of the most significant donor to the arts in a transparent but successful attempt to gain positive PR-by-association. Perceived cultural good will is important in any era, but essential in times like these when the financial sector and big business are regarded as especially villainous. I don’t condemn corporate backing; I just want curatorial integrity to remain in tact.

Further Reading:

- “Corporate Sponsorship A Growing Area of Arts Concern” AllBusiness.com, October 2000

- “Fashion Victim,” NYTimes.com, May 6, 2005

- “Ethics and the Visual Arts” edited by Elaine A. King, Gail Levin, Allworth Communications, Inc., 2006

- “Establishing Dress History,†Lou Taylor, Manchester University Press, 2004

- “Patronizing the Arts,†Marjorie Garber, Princeton University Press, 2008

- “Night at the Museum Smithsonian’s PR bonanza†NPR.org, May 21, 2009

- “Smithsonian Hopes to Cash in On Stiller Movie†NPR.org, May 21, 2009