One of the few advantages of working in midtown is that I am just a couple minutes jaunt away from the MoMA, and every once in awhile, I actually take my full hour lunch break to soak up some visual culture. Yesterday I fought my way through the rainy day museum-attending mob (I believe it’s also free admission day) and attended a walking tour delivered by the stunningly beautiful and articulate Galia Fischer on one of my favorite artists, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and his series of 11 Berlin street scene paintings, created 1913 – 1915 (a period I particularly love in fashion history, especially as it relates to pre-war times). Kirchner is known for his harsh, sweeping vertical lines, violent brush strokes and dismal color schemes (I say “dismal” adoringly), not to mention his frequent subject of prostitutes (which in the scheme of art history is far from uncommon, but I’ll just throw it out there). To begin at the beginning:

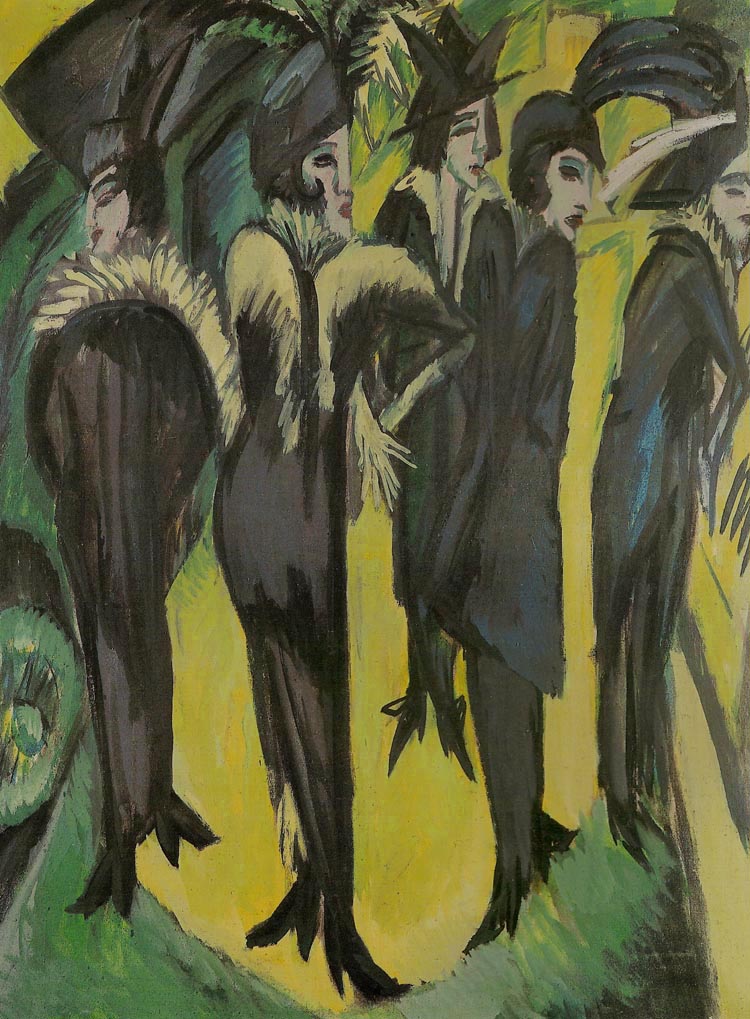

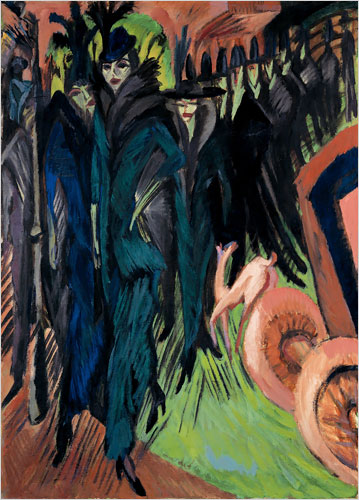

“Five Women in the Street” (1913) was the first in Kirchner’s street series, and depicts the ladies of the night as birds of paradise (or perhaps a more domestic parrot), posing in their green habitat with green-tinged millinery plumage and greenish skin. The bird comparison is further emphasized by the bulky fur lapels that puff the chest area up, and the hobble skirts — both of which were popular fashions in the 19-teens — that coincidentally create bird-like, tapered legs and emphasize pointy feet.

The women peer into what can be assumed to be a storefront on our right (the dark hash marks presumably the glass reflection) window shopping, while it may be inferred that the car sidling close on the left contains a man cruising through his own glass at the bodily merchandise they are displaying and hocking.

I really love the complex relationship between Voyeur and The Observed that windows and glass bring up. There are several great essays that deal with this topic in Sexuality & Space, published by the Princeton Press, specifically Beatriz Colomina’s “The Split Wall: Domestic Voyeurism” that discusses how architecture and constructed spaces can create nooks, for example, that feel cozy and safe but are actually framed like a stage, displaying rather than concealing. Additionally, there is the layer of interior/domestic spaces being considered inherently feminine. Though I’m delighted that “Five Women,” with its plein air ladies and automobile-hidden man, contradicts that convention in one sense, the way Kirchner has framed them hints at a more complex relationship. The women are sandwiched tightly between the car and the window, and they touch the very edges of each side of his painting, suggesting that they’re boxed in (within their profession, within their greater role as women, etc.), even within their literal outdoor setting.

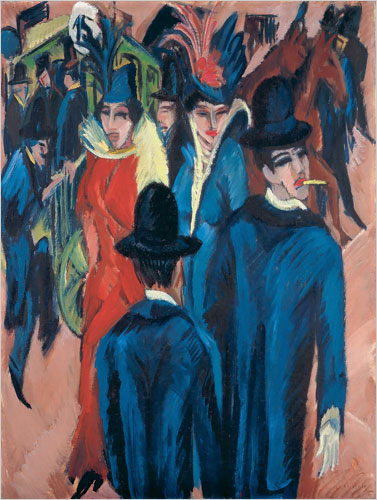

“Berlin Street Scene” (1913) has a wider array of colors than many other of Kirchner’s street scenes. There are actually visible men in this one, but they are all made rather anonymous by their unvarying blue-black coats and high bowlers. By contrast, the two women become the focus by color alone; though they are half hidden by the two men, the woman in scarlet and her companion in bright blue pop out. The woman-as-bird theme continues with the feathered hats, but this is a male perspective, I think. What’s more telling about the closeness of the women’s relationship is that their hats match their companion’s coats and not their own. This unifies them chromatically and implies their connection within the sea of dusky men, though they look away from each other. As I went through the show, I realized that this was a favorite visual trick of Kirchner’s.

Galia pointed out that the face of the man we can actually see appears to be almost as grotesquely made up as the women’s: he has those smudgy kohl eyes and lips that match the woman in blue’s. I like to imagine a little narrative: that those are two johns approaching the prostitutes but as they near, the one on the right turns away in disgust, twisting his body in a most awkward way so you almost can’t tell which way his body is facing. But is he repulsed by the hookers (you must admit the one on the left, with mascara actually dribbling down her face, is not looking so appetizing), or himself? Remember this is pre-WWI era, when gender roles — specifically in Berlin — were slowly being muddled as men went off to war and women took over their jobs, and by extension their social roles. Though Berlin had (and has) a notoriously gender-experimental population, there seems always to be an underlying fear of feminization (and by extension, castration) fear held by men when ancient gender roles are blurred. This particular man seems to be holding onto the last shreds of his masculinity with the sickly yellow, phallic cigarette dangling from his displeased mouth.

“Potsdamer Platz” (Square) (1914) has a color scheme I love: the chili pepper-red train station dominates the upper register while avacado/lime green streets slice through the lower half of the painting, somehow making even the round island the prostitutes stand on appear pointed. The green seems to be literally reflected in the faces of the women as they stand on their perch (anther bird illusion?), with a healthy smattering of murky beige to soften the total effect of the scene… slightly.

The woman on the left is ensconced in severe black, with a flat black hat that was not a popular style (fashion historians, correct me if I’m wrong) at the time; in fact, it more closely resembles hats of the 1940s, another war period. The broad hat becomes a platform from which to drape the oddly straight veil, whose evenly spaced vertical folds create quite a birdcage (that old theme again!) around her head, an effect punctuated by the white plumage atop it all. This ensemble approximates mourning clothes — the white of the hat feathers and the collar would have been inappropriate for true mourning-wear, but I liked Galia’s hypothesis that the prostitute was possibly attempting to elicit sympathy (and clients?!) from this odd costume choice. This, after all, was the first year of WWI and there were increasing numbers of pitiable widows on the streets as husbands, brothers and fathers were killed.

The two elongated streetwalkers appear (ironically) stationary as they are surrounded by briskly striding men in black. As with other Kirchner street scenes, the women fill the the frame from top to bottom, this time literally dwarfing the insignificant men portrayed in distorted perspective, 1/3 their size. Interesting that the monumental women seem to be stagnating in a world of men with places to go, trains to catch, etc. Social commentary, hmmm?

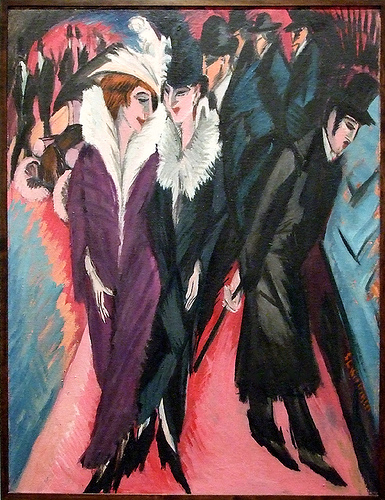

“Street, Berlin” (1913) has a very different color scheme from the others. The purple dress, flamingo pink street and turquoise background are oddly fresh, if still slightly unnatural, shades. The women’s smirking bubblegum pink faces are turned in conspiratorially toward each other’s again. A man is in the foreground with and the same size as the hookers for once, and though he leans away with his whole body, looking down and away, his sneaky cane projects from his general crotch area and practically touches the woman on the right. The fleshy path they all stand on parts in a cleft between the two figures and is emphasized with an outline of deeper red. The prostitute in purple’s plunging plum coat with the fur lining, not to mention her hand which simultaneously conceals and draws attention to her own groin further drives the sexual context of this painting home.

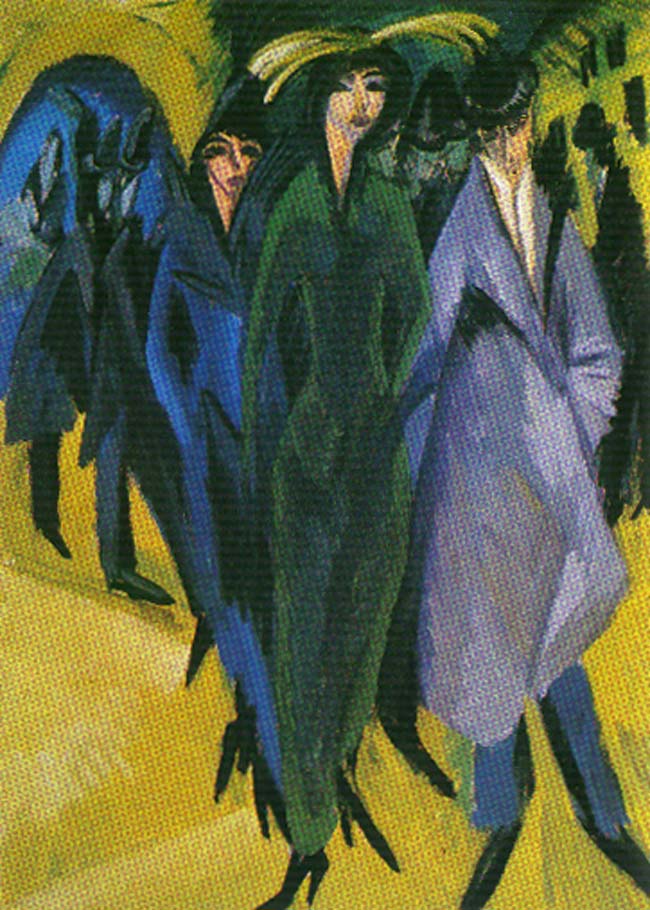

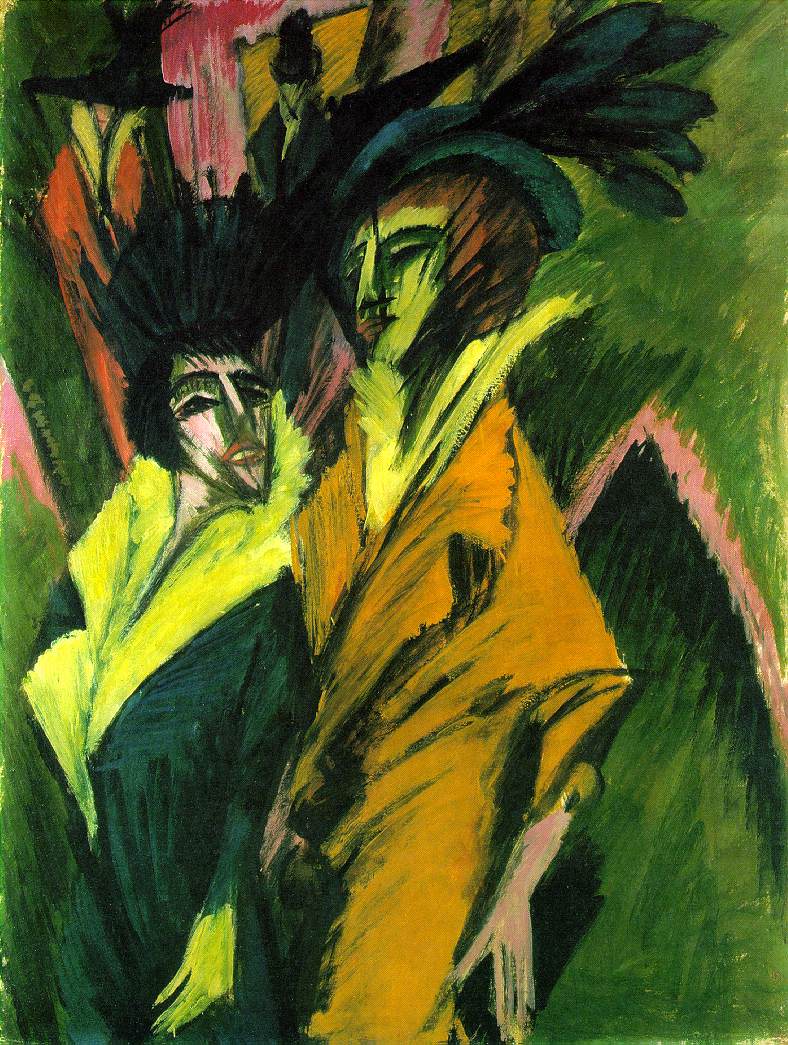

“Women in the Street” (1915) has startling chartreuse background with dark forest green dress and deep blue dress worn by the familiar prostitutes, framed centrally again. A rather effeminate man stands to the right, almost blending with the women, but his trousers peeking from beneath his coat and his bowler hat reveals his true sex. He looks demurely down in the direction of the woman in green’s feet while she and her companion stare boldly at us, upsetting traditional viewing gender rules, while calling attention to the viewer’s own participation in the voyeuristic game.

“Two Women in the Street” (1914) distinguishes itself from the rest of the series in several ways. First, it’s a close up, showing only the torsos of the women (who again, dominate the frame). Second, their faces are abstracted and flattened with unnatural striations resembling wood grain in an (uncredited — apparently Kirchner rejected any suggestion that his work was influenced by anything!) homage to the African art that was flooding Europe at that time; Picasso was similarly inspired in the early stages of his career. Even with this truncated view, the women are unified by their identical postures. And again, the woman in the tangerine coat wears a hat the color of her companion’s peacock turquoise coat; their matching lemon yellow collars unify them with pose and color.

“Street Scene” (1914) was the final painting in the exhibition. It too contains the now familiar motif of two women wearing hats matching each others’ outfits (a little hard to make out in this picture, I think): in this instance, the dusty turquoise with royal blue hat paired with her companion’s royal blue coat with turquoise cap. And again, they stand so close, belly to belly, with one elegant leg apiece stretched out in front, one tucked behind, so that they might even be mistaken for one person. I don’t have a clear reading on their smirks: do they imply power, or act as protective element?

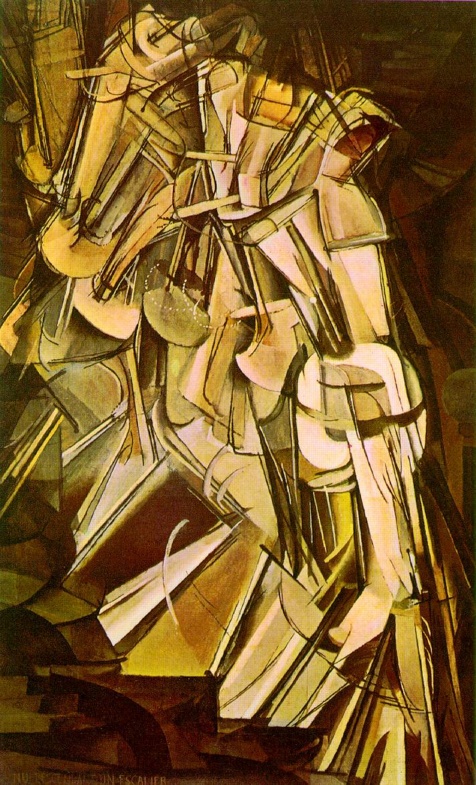

The men behind them line up so neatly that they resemble a female chorus line, especially with the expertly pointed toes. This is also an obvious reference to chronophotography, the Victorian precursor to moving film recording as we know it, where photographs were taken in quick succession in an effort to capture a subject’s movements. These early photos inspired the Futurist art movement and one of my favorite Duchamp paintings, “Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2,” and I can see similarity with Busby Berkley‘s large scale musical numbers from the 1930s involving identically (scantily clad) dancers moving in near synchronization so as to give the illusion they are all connected. Though he is more famous for his dancing girl numbers, there were also large male chorus lines. As with Kirchner’s street series, Berkley’s dance numbers were highly sexually charged, with scantily clad women opening and closing their arms and legs suggestively; the irony is that Kirchner has once again feminized the men by posturing them thus.

Continuing the sexual theme here are the phallic, creamy pink car wheels in the lower right hand corner that touch the actual bottom– complete with red slit– of an identically colored pink dog.

Lastly, there is a mostly hidden, murky man who I like to imagine is the pimp of these women. He wears a gray suit as opposed to the chorus mens’ black attire, and his dusty turquoise hat ties him to the women with color, as they are tied to each other.

1 comment

Gokhan says:

Jan 27, 2011

Love that painting,,,