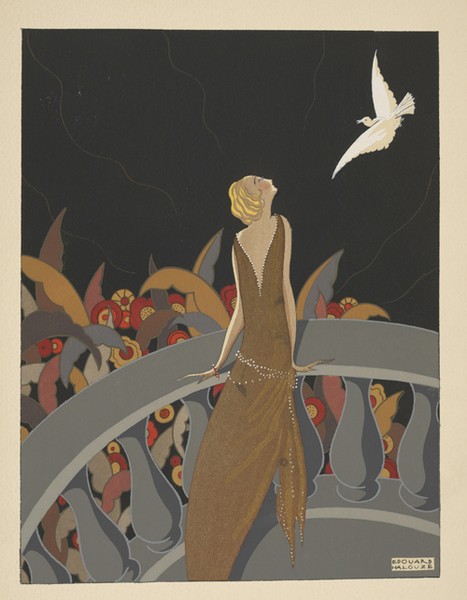

Yesterday I attended a lecture at the New York Public Library accompanying their current exhibit “Art Deco Design: Rhythm and Verve.” There was another lecture on art deco architecture that I attended a few weeks ago, but this one– “Fashions of the Art Deco Era”– was tailored for me. Paula Baxter, curator of the exhibit and author of one of my absolute favorite fashion blogs, was the speaker. Though fashion was the focal point, Paula’s (and my) interest in the sartorial arts lies in the socio-political and economic climates surrounding fashion, so much of the information disseminated was not strictly clothes-related, but provided a groundwork for why fashion took such a radical turn in the “teen-aughts,” as Paula delightfully calls them. This emphasizes the point that nothing is invented or occurs in a vacuum, and all local and often world events exert direct influence upon visual arts, fashion most certainly included. I will relay my notes here, with perhaps a few tangents of my own.

Art Deco’s lifespan was from 1919 – 1939. Here is a limited time line overlay:

1914-18 WWI

1920 – 19th Amendment grants women suffrage

1923 – Yankee Stadium built

1924 – Native Americans granted US citizenship

1926 – A. A. Milne writes Winnie the Poo

1927 – The Jazz Singer is the first full length talkie

1927 – Charles Lindbergh flies the first non-stop flight from New York to Paris

1929 – stock market crash heralded the Great Depression

1931 – Empire State Building completed (and struggles to procure tenants)

1930s – electric sewing machines widespread (invented in 1889)

1939-41 – WWII

The end of WWI marked a shocking new era for the world. Women’s public roles had increased out of necessity during the war and the overall jublilation of victory translated into a great departure from Edwardian social mores, sexual roles, decorative arts and fashions. Most are familiar with the neck baring bobbed haircut of the 20s, but Paula noted that it was not just a fad, but a scandal– women had worn long hair for centuries, and cutting a pageboy ‘do was like tattoos are today. Many adopt the fashion, but just as many scorn the trend as frivolous or scandalous (many parents among the latter group). As a side note, I sported the Louise Brooks bob (above) for a decade.

In painting and “high” art, the Cubist movement had a tremendous impact upon fashion (the Metropolitan Museum presented the compelling evidence marvelously in their 1998-99 exhibit “Cubism and Fashion” in which paintings from the period were juxtaposed with fashion examples side-by-side). Inspired by African sculpture, by painters Paul Cézanne (French, 1839-1906) and Georges Seurat (French, 1859-1891), and by the Fauves, Cubists shattered, analyzed and reassembled the subject matter into abstracted forms. This aesthetic inspired and was adopted by designers of all kinds– furniture, textile, and fashion, who distilled their own creations to streamlined versions of more ornate, familiar forms of the Edwardian and Victorian ages. Embellishment and ornamentation was more restrained, and dress patterns were reduced to simple shapes (i.e. squares, circles, cylinders, etc.) that were allowed to drape naturally on the body, rather than restrain it with restrictive tailoring.

Jazz

Increasing acceptability of women playing sports and leading more active lifestyles had great impact on the changing desired physique of the 20s. Silhouettes from the then-recent Edwardian and Victorian ages were highly curvaceous– if not downright meaty– with emphasis placed on overflowing bosoms, hips, and buttocks. But the skimpy fashions of the 20s complimented the new emphasis on athletic bodies and narrowed the gap between health and glamour. (As a side note, Paula said yes, skirts were shorter than they had ever been, but even in 1925 when hemlines were at their shortest, they were still 1″ below the knee.)

Menswear continued the Edwardian penchant for proper, dapper, tailored suits. The new found athleticism made the ideal male figure sleeker than times past, too. Paula emphasized that the Duke of Windsor (the temporary Prince of Wales) had a tremendous influence over men’s fashion of his time, disseminating his personal stylistic choices by being the most photographed celebrity of his time. He popularized cuffed trousers and advocated for the switch to the zipper fly from the buttoned version. The zipper took its modern form in 1913 from its more finicky 1893 version which had a tremendous impact on the making of clothes and the act of dressing, but I believe it was the Duke’s vocal endorsement of it for easy access to the groin (I’m quite sure that wasn’t his exact argument) that caused a sartorial uproar and resistance before ultimate widespread adoption.

The 20s was when America’s obsession with celebrity fashion and idolization began. With the talkies of the silver screen, images of stars like Clara Bow, Fred Astaire, and Marlene Dietrich were disseminated across the United States and internationally. The film studios invested much in their publicity departments which took tremendous pains to create and present their stars in a flattering light, blurring the lines between personal and private life.

The introduction of feasible air transportation with Charles Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis flight (see time line above) continued the craze for all things streamlined and aerodynamic, which, again, was translated by designers and disseminated into everyday objects like martini sets and fashion. It also marked the beginning of America’s dependence on credit and oil.

After the world became choked by the Great Depression with the dawn of the 30s, hemlines dropped to more conservative lows. Flared skirts and an emphasis on waists replaced the straight lines of the 20s, though the ideal female figure continued to be relatively flat, hipless, and generally boyish, a puzzling trend of gender ambiguity that continues to this day.

Marlene Dietrich was one of the few who managed to assert her personal style in spite of loud protests from her employers, sporting mannish pantsuits (Hillary’s predecessor!) in addition to more conventional slinky gowns. It was only because her sex appeal

By the 30s, the widespread usage of the electric sewing machine had resulted in plentiful off-the-rack merchandise. Madeleine Vionnet was credited with inventing draping on the bias, a technique that enables fabric to hang and stretch more naturally over a body rather than dictate a shape. She started a fad of elegant gowns that clung to the necessarily slender forms of the wearers, requiring even less additional accessorizing than the flapper dresses of the previous decade.

The menswear silhouette departed similarly from the sleek but narrow to one that emphasized broader shoulders, slim waists, and wider pants legs, a la Clark Gable. With the approaching of WWII and ever more women entering the workforce, gender lines continued to blur. Menswear influenced women’s fashion in the 30s with tailoring becoming evermore important to both sexes; women would feminize their skirt suits with ostentatious bows that belied the inherently masculine suits that was appropriate work wear for secretaries, etc.

1 comment

motozulli says:

Apr 2, 2009

Huh. I never considered that the electrification of sewing machines had that much impact on mass production. What’s your source? I’d like to read up on this