In preparation for the upcoming Textile Association of America symposium I’m presenting at later this week — “Textiles & Politics” symposium — I’ve been doing a lot of research on our country’s history of using yarn crafts — specifically knitting — as a political act rather than merely a domestic or social one.

Primarily a feminine duty or pastime, knitting has a deliciously rich history of political subversion. For example, as Britain levied higher and higher taxes on its colonies in the 1760s, Americans made their displeasure known by weaning themselves off imported British goods; they officially banned British imports in 1769. In addition to British tea which, of course, resulted in the infamous Boston Tea Party revolt (1773), Americans had previously relied upon many imported English textiles to clothe themselves. Since the previous decade, women would discuss the unconstitutionality of the Stamp Act (1765) and put their hands where their mouths were, holding political meetings veiled as innocuously named “spinning meetings†or “spinning bees” where they could participate in political discussions while spinning yarn and thread, sewing, and knitting items to clothe their families and communities in lieu of British fiber goods. Otherwise excluded from political participation or assembly, it was especially extraordinary that entire communities — including men — rallied around these spinning bees which developed, against all odds, into spectator sporting events, with good-natured competitions: between church congregations, married and unmarried women, towns and cities, and old and young. Patriotism was attributed to the “Freedom, Liberty, and Frugality†of those industrious women who could clothe themselves and their families in homespun and recycled garments from head to toe.

Women thus became accustomed to clothing their families with homespun and hand-knit textiles, so it was a short leap to providing their men uniforms when America finally went to war with England in the Revolutionary War (1775-1783). Congress appointed a Clothier-General to assess and fulfill the army’s needs including clothing and blankets. The burden of fulfilling these supplies often fell to towns, some of which published names and tallies of knitters and their output, to encourage healthy competition and increase production. Some women added relevant artistic touches such as “1776†knit into socks from that fateful year. In the lowest moments of the war, with some unfortunate soldiers reportedly going naked, some industrious women would round up blankets, yarn, and worn-out clothing which they would patch and darn, unravel and knit into “new†stockings, shirts, breeches, and blankets, transporting these supplies themselves to the front for distribution — as “harmless” women, they were able to slip past the British more easily. Women’s patriotism thus became bound with their ability to knit and clothe larger and larger groups of men.

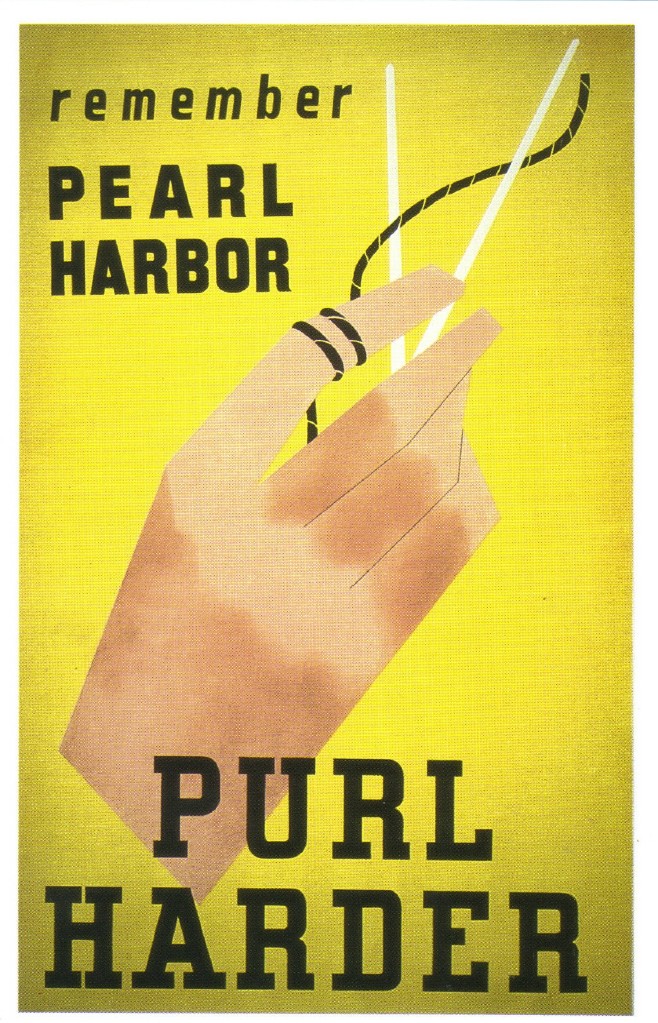

Over the next few centuries, knitting enjoyed resurgences at almost every major American war (“Knit for Victory!”), though with the Industrial Revolution of the 19th century, most peacetime spinning and textile creation moved from the home to factories. My favorite World War II poster incorporates a knitting pun clearly aimed at galvanizing women in the war effort in that particularly feminine handicraft:

I find this poster an especially suspect appeal as knitting machines were far more efficient than hand-knitting, begging the question: was this an attempt by men to instill patriotism in their women while deliberately suggesting they occupy themselves with a feminine chore — I mean honor — perhaps to balance the masculine characteristics they were presumably adopting while performing menswork in factories?

Skipping ahead another few decades….

Since 9/11, there has been a youth-driven revival of yarn arts, a statement against mass production and a reclamation of women’s crafts, contentious since the ’80s as anti-feminist. Contemporary activists have begun incorporating large-scale knit and crocheted pieces into political public art statements. Often called “yarn bombing†or “yarn graffiti,†these installations may beautify public spaces and add a touch of the handmade to our industrialized environments – drab urban landscapes are the usual targets—if temporarily. More overtly political yarn bombers may target military tanks or relevant statues; for example, Marianne Joergensen stitched a pink blanket over a combat tank to protest Denmark’s involvement in the Iraq war in 2006:

The squares were knit and crocheted by volunteers from Denmark, the UK, USA, and other countries, a collaboration hearkening back to the knitting / spinning circles of earlier centuries. Joergensen writes:

“Unsimilar to a war, knitting signals home, care, closeness and time for reflection. Ever since Denmark became involved in the war in Iraq I have made different variations of pink tanks, and I intend to keep doing that, until the war ends. For me, the tank is a symbol of stepping over other people’s borders. When it is covered in pink, it becomes completely unarmed and it loses it’s authority. Pink becomes a contrast in both material and color when combined with the tank.”

The comforting, cozy, handmade quality contrasts awesomely with the cold mechanics and implied violence of war machines, does it not?

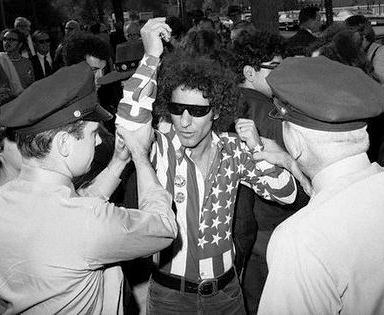

Lisa Anne Auerbach’s Steal This Sweater (an homage to Abbie Hoffman’s anarchist Yippie manifesto Steal This Book of 1971) similarly provides knitting patterns for leftist political message garments, such as “Body Count Mittens†that list Iraq War death toll counts within a traditional graphic intarsia motif:

Knit artists are not limited to wool or cotton yarn these days. My fellow panelist Adrienne Sloane‘s pieces, “Uncle Sam’s Tea Party” and “Cost of War” refer to the historical relationship between women, knit goods, and war, and make explicit her feelings of dread, violence, and wastefulness of human life in America’s current War on Terror (click to view larger images):

My other fellow-panelist, Ruth Marshall, addresses violence against a different population: animals. She knits elaborately detailed renditions of animals whose species have become endangered due to illegal harvesting for their pelts. The Amur leopard is the most endangered big cat in the world; Marshall has painstakingly mimicked a stretched skin of one with harmless yarn (click to enlarge):

Her work very much reminds me of a project I’ve had in my Ravelry.com queue for ages (admittedly, this has a bit of humor, I think); a faux fox stole:

Contrary to its innocuous grannie associations, knitting can politicize.

————————————————————————-

I will be speaking about this topic in greater depth (the French Revolution!, WWI & WWII!, the ’60s and ’70s feminist revival!, post-9/11 craftivism!), along with two contemporary knitting activists Adrienne Sloane and Ruth Marshall at the Textile Association of America’s “Textiles & Politics” symposium this September 19 – 22 in Washington, DC (our panel is on Saturday, 10.30am). Drop a line if you’re planning on coming, I’d love to meet you!

Further Reading:

- Museum of Art and Design exhibit Radical Lace and Subversive Knitting

- No Idle Hands: The Social History of American Knitting by Anne L. Macdonald

- The Culture of Knitting by Joanne Turney

4 comments

Yolanda says:

Jan 27, 2020

Fantastic blog! Have you produced a book? It would be so worthwhile! 😀 This is such a great resource for textile and fashion students everywhere!

mojo says:

Jul 18, 2019

I have always liked fibre and assorted yarn.

Erica Bates says:

Aug 10, 2013

The Australian Knitting Nannas Against Gas,(KNAG) founded in the Northern Rivers area of New South Wales in mid 2012 has become a global phenomenon, linking women around the world in non violent protest against Coal Seam (shale) gas and inappropriate mining. Knitting Nannas sit peacefully at blockades, knitting and crocheting while blocking trucks on the road or entry gates to sights. Even the Police are charmed by their peaceful style of protesting. Good humour and gifts help ;). As recently as ths past week on 8th August 2013 a facebook event called the Global Knit In OZ for Balcombe was conducted in solidarity with the women of Sussex England who are facing fracking and shale gas production in teir beautiful countryside. Women from 4 continents anticipated, sharing photographs of their reasonable knit ins and their well wishes and compassion with their sisters in Balcombe. For more information and a copy of the wording of the “Nannafesto” by which all KNAGs are bound, visit their Facebook site .

Joy says:

Sep 20, 2012

knitwear does seem to have a historical anchor in feminism and activism.