As you may or may not be aware, the auction of Debbie Reynolds’ extensive Hollywood costume collection was (not surprisingly) a smashing success, in that it set new new highs for what collectors would pay for literal fabric of Hollywood history. Items that have been reported on most have included:

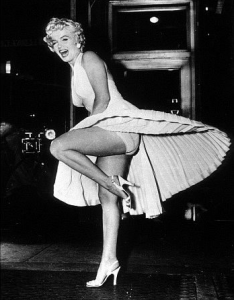

- $4.6 million for Marilyn Monroe’s white subway dress from The Seven Year Itch (1955; costumes by Travilla):

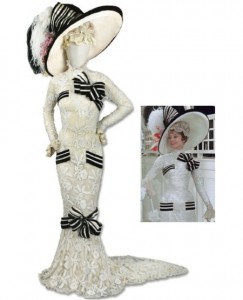

- $3.7 million for Audrey Hepburn’s Ascot race dress in My Fair Lady (1964; costumes by Cecil Beaton):

- $910,000 for Judy Garland’s Dorothy screen test dress from The Wizard of Oz (1939; costumes by Adrian):

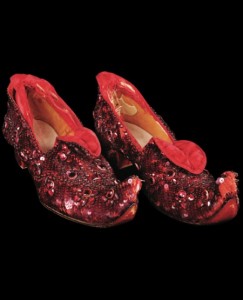

- $50K for Judy Garland’s Dorothy ruby slippers from The Wizard of Oz (these actually look like the shoes as worn by the Wicked Witch of the East, and not Dorothy, to me):

- $100K for Elizabeth Taylor’s headdress from Cleopatra (1963; costumes by Vittorio Nino Novarese and Renié):

Some items that were not so popular were some pantaloons from Mutiny on the Bounty (1962; costumes by Moss Mabry) and a lock of Mary Pickford’s hair (this is indicative of the under-valued silent screen era, I think– Ms. Pickford was one of the most popular actors of the silent era, though few remember her name now, even as a founder of United Artists Pictures production company). Predictably, few articles about the auction results even mentioned these low-sellers.

An interesting peculiarity about costumes is that they are generally made in multiples, as they experience accelerated wear-and-tear from being changed into and out of, often hurriedly between scenes. This sets it apart from most art forms (excepting photography and screen-painted pop art, for example) which prize the uniqueness of The Single Object.

People often conflate worth and importance with monetary value, a result of America’s aggressive capitalistic leanings. One of my favorite moments in The Thomas Crown Affair remake (1999) was during the opening museum sequence where a teacher is desperately trying to wrangle the attention of her disinterested class; after unsuccessfully trying to impress them with historical details about Monet’s San Giorno Maggiore at Dusk (1908) she finally says (I’m paraphrasing): “Get this: it’s worth a million bucks.” Her young audience snaps to attention at the mention of money, and collectively gasps, their attention suddenly focused. They have been brought up in a culture that values money above all else — including personal preference, historical import, quality or craftsmanship. If some wealthy patron is willing to blow a wad of bills on some painting, the press attention it receives increases exponentially, as does the public opinion of the work. Money subjugates all other artistic criteria.

Valerie Steele, in a NYTmes article from earlier this year which explored the rather tiresome question of whether fashion objects are museum-worthy, astutely noted:

“Most museum administrators are not particularly keen on fashion because it is not generally considered art, and these shows do take place at art museums…. Of course we realize that art is commercial, but it has a reputation for transcending that, whereas clothing does not” (my emphasis).

This commercialism is precisely the value system that leads to “fast fashion” — if a temporarily trendy skirt costs only $15 at (non-Unionized) Target, it’s easier to discard it after a season or two because the buyer doesn’t feel she’s throwing very much money away. This kind of monetary thinking omits the ecological impact of this careless behavior (an estimated 9.8 million tons of textiles were generated in 2001), and subjugates personal preference and individual style to fashion runway schedules and retail seasons which all promote planned obsolescence. But I digress….

I suppose what irritates me about this whole costume auction business is not that these garments do not deserve the press attention, or to be preserved or collected in the first place, but that it is only newsworthy if there is an impressive price tag to report on — articles almost always omit costume designer, technological film context, world politics of the day (which always imposes interesting constrictions on fabric availability, sexual mores, etc.), in favor of attributing all “worth” to the famous bodies these items hung on in one of the last stages of a costume’s long life. In the most basic, visceral sense, isn’t it utterly disconcerting to see the Dorothy dress divorced from its film environment? Compare the flattened, empty dress in the first photo of this post to the dress on Judy Garland’s body, within the Wizard of Oz environment:

For me, the Dorothy dress is significant as an iconic piece of a film with breakthrough technology (color and black-and-white film in 1939); not to mention its powerful juxtaposition of the harsh Great Depression reality (Dorothy on her Kansas farm, portraying the devastating Dust Bowl that swept American and Canadian plains in the ’30s) with the fantasy dream world of ultimately rewarded optimistic aspirations. It differed from most ’30s Hollywood films where the Great Depression was completely omitted and a wealthy and/or comedic alternative reality was portrayed in lighthearted slapstick comedies and musicals. Dorothy’s gingham dress signified her farm heritage and her youth, while the ruby slippers were, in addition to being sparkly and fancy, were heeled, hinting at Dorothy’s needing to grow up. The literal contrast of texture and color between the blue cotton dress and spangly heels echoed the uneasy transition from innocent immaturity to worldly, grateful young woman. (Says me.)

Few articles have bothered mentioning the designer of auctioned costumes. It is extremely possible that many familiar with the “Marilyn Monroe dress” don’t even know it was worn in The Seven Year Itch (1955). The photos we see of this dress most often are actually from saucy publicity shots of Marilyn ineffectually hiding her panties while standing over a wind turbine-equipped subway grate, eclipsing the film itself — in which she was only filmed from the thighs down briefly (no underwear shot at all), and mostly from the waist up, due to censorship issues (as Elvis Presley’s gyrating hips were similarly cropped out of a ’50s performance).

Film posters had fewer restrictions, and so could get away with posters like this:

Though I admittedly haven’t gone too deep into the histories of these garments, I have not even found an attempt to deepen the public’s understanding or appreciation of costumes in any article about these costume auctions, and once again, I feel that fashion has been given short shrift as an effective cultural educating tool, relegated instead to the realm of quaint prettiness, and graded by money spent to own it.

1 comment

edgertor says:

Jun 21, 2011

btw, this actually happens with the subways in motion in manhattan–one has to be careful walking over grates while wearing full skirts If you hear a train coming–i’ve accidentally gotten the marilyn treatment on more than one occasion.