Poverty and Power: Secondhand Clothes as Protest

by Tove Hermanson on Apr 11, 2012 • 10:11 pm 2 CommentsLater this week I will be giving an extended lecture on the secondhand fashion market and countercultures that adopted thrifted clothes as political statements — focusing on Yippies, but touching upon the Beats — at this year’s Pop Culture Association symposium in Boston, MA. My panel will be on Thursday at 4:45pm, and there will be a robust line-up of other fashion panels on topics covering Fashion, Style, Appearance, Consumption + Design. Drop a line if you’ll be there — or just look out for me, I’d love to meet you!

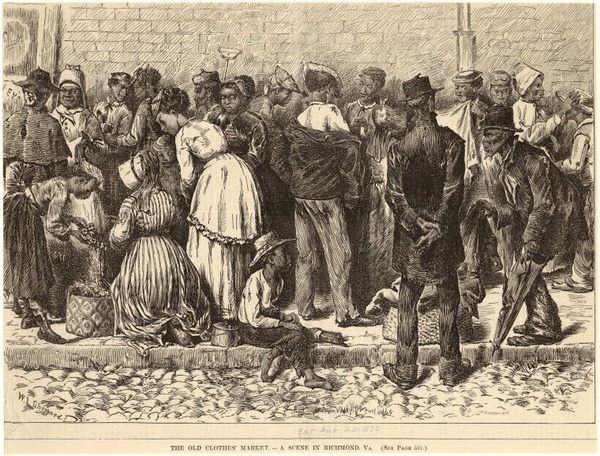

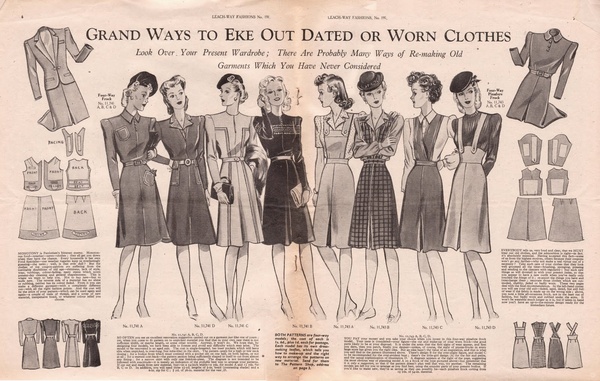

As early as the 17th century, servants and slaves sold their wealthy employers’ castoff garments at secondhand depots to other impoverished people. You can see from the depiction above (click for larger image) that secondhand markets were frequented by shabbily dressed people: the poor and/or racial minorities, who would not have the money for expensive new fabrics, nor the leisure time to sew anything but mending. Used clothes accordingly carried a heavy stigma of poverty and desperation — written accounts sometimes refer to the silence at these markets, no person wanting to draw attention to him or herself. But during WWII, when most people — even in wealthy countries — were struggling to make ends meet and to clothe their families, the American and British governments actually encouraged their citizens to “Make Do and Mend.” Magazines and newspapers like the following would actually dispense advice on how to reduce spending and recycle what you had:

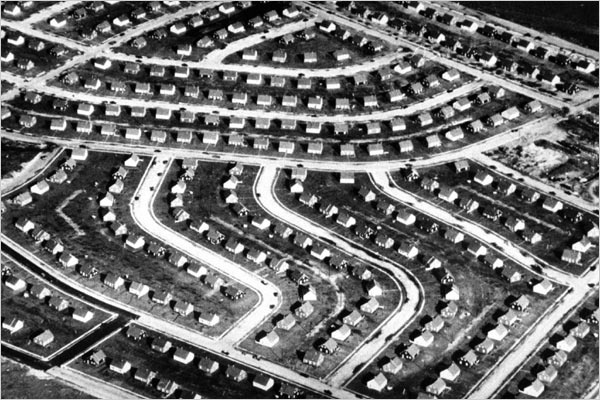

It was only when the economics of Americans leveled out a bit in the economic boom of the ’50s and ’60s that castoff garments acquired an entirely new significance: that of protest against the societies that perpetuated this kind of wealth disparity.

In the mid-20th century, American and European youth subcultures adopted secondhand clothes as aesthetic protest against the excessive consumerism of older generations who spent their new-found leisure time in the first controlled environment shopping malls, and populating the idealized new homogenous suburbs like Levittown, Long Island:

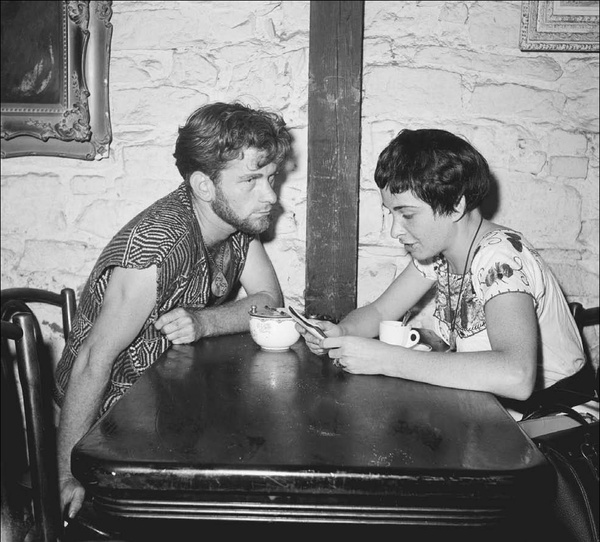

Often galvanized by a rejection of their respective contemporary political systems and social mores, beatniks, hippies, and punks all rejected elitist designer fashions for ideological reasons. Embracing the very stigma of used clothes, secondhand style enabled wearers to confront the mainstream public by advertising allegiances to anti-consumerist lifestyles and radical socio-political philosophies. Existentialist beatniks adopted an understated, muted uniform with references to French existentialism (stripes, berets, etc.) and peasant blouses, in contrast to polished mainstream ‘50s colors and flamboyant silhouettes:

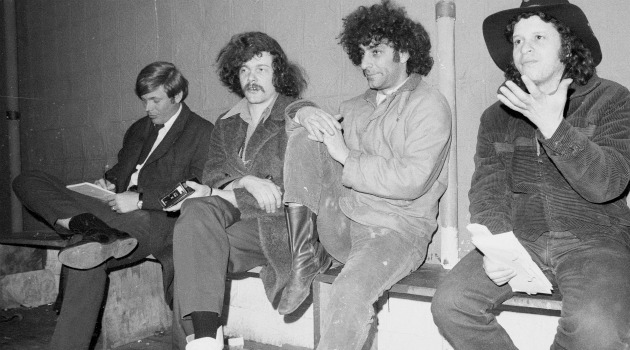

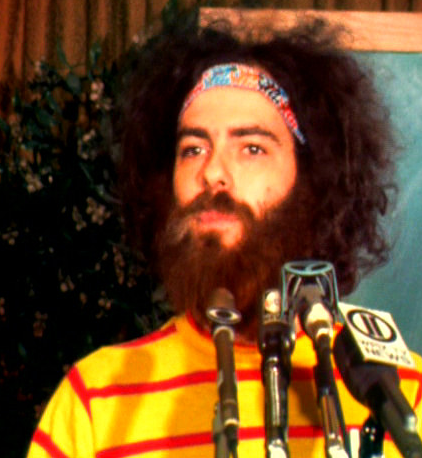

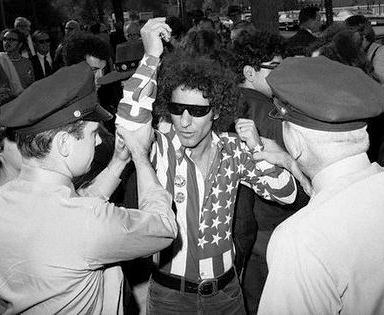

Similarly, Marxist-leaning hippies and Yippies revived outmoded styles with flowing layers in contrast to distinctly futuristic space-race minimalist ‘60s designs

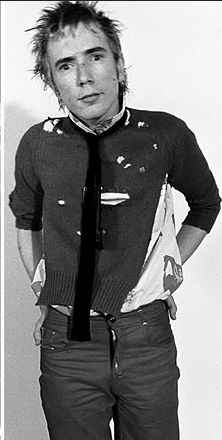

This tradition continued with the anarchist punks who sported visibly ragged, sloppily mended clothes in contrast to ‘80s polished business chic:

In all these instances, secondhand fashion enabled radical groups to sidestep a major consumerist cycle, and to publicize the implied politics of the rejection of wealth accumulation. By wearing clothes worn and donated by middle-class and wealthy “straights,†beatniks, hippies, and punks were able to imbue those garments with new radical symbolism. There is clearly much more to the story of the secondhand clothes — not least of which is the contemporary practice of outsourcing the manual labor and bottom-of-the-barrel “rag” pickings to developing countries like Hati — but sidestepping the fast fashion whirlwind with responsibly acquired used clothes seems like a step in the right direction.

2 comments

mojo says:

Jul 3, 2019

Poverty is a major issue in our world today where people cannot afford the basic necessities required to survive.

dee fairchild says:

Jul 11, 2012

just found your blog, wow, so interesting!

i took a class in eco garments 2 years ago and now design zero waste/zero wash garments – though as i tend to drop food on myself, that’s low wash…;) really interesting the huge constructs around clothing…

all good wishes

dee @ birds sing artblog