I recently gave a lecture on cross-dressing to a terrific sociology class at FIT, and I had such ridiculous fun (and stress!) researching it that I thought I’d share with the blogosphere to spread the wealth. You don’t get the pleasure of my witty repartee, but you do get a decent, if slightly inferior, substitute. I do want to give the disclaimer that this is not even close to a comprehensive, in-depth study of cross-dressing, but rather a quickie pictorial romp through the ages. This is “cross-dressing” very loosely defined: the fashions included are technically male fashions worn by men, but have distinct feminine qualities that were widely adopted, but also criticized by an endless list of moralists. Lastly, am also concentrating on Western fashion, which is, I acknowledge, an additional shortcoming of this essay, with the Eastern cultures embracing bisexual skirts for so long. So be it. I included examples of both clothing that was actually considered cross-dressing in its own day, and garments that were perfectly hetero-normative then, but appear to be borrowed from the opposite sex to our modern eyes.

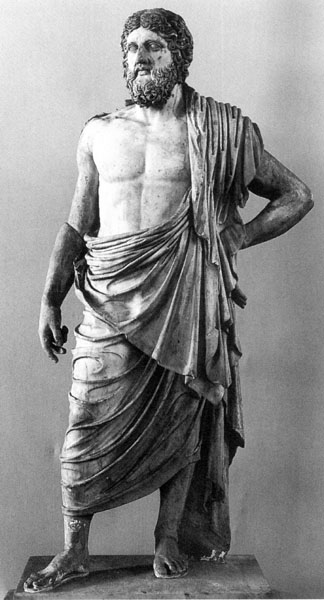

I’m not going to spend much time on the ancients, but I would be remiss if I didn’t point out that it took many hundreds of years to develop sex-specific clothing styles, and though the ancient Greeks and Romans from which we came did have differentiation between sexes in their draped garments (the women’s breasts were covered while men’s chests might be exposed, for example), those variations were relatively slight, immediately drawing attention to the fact that sex-specific clothes is a societal construct that was honed — as gender roles and expectations were — over time. Mighty, manly Zeus (below) wears a draped himation that could be just as easily worn by a woman, were the front flap pulled up for modesty:

The Medieval houppelande was a loose bodied, floor-length coat with narrow sleeves that became a symbol of gender non-specificity in the late 14th/early 15th centuries:

Men wore jewelry off and on, and in the mid-16th century, they often wore a single dangling earring along with their wide, padded breeches that resembled puffy skirts. Whatever femininity this might have indicated was counter-balanced with hyper-masculine pointy beards and codpieces (which were not uncommonly erect, in case you had any lingering doubts of a man’s virility). The pointy beard mirrored the triangular waistline, and punctuated by the essential phallic sword accessory, further drawing the eye to the crotch:

It has been hypothesized that the exaggeratedly stuffed breeches of the 16th century was a sartorial salute to (or at least an acknowledgement of) an age of powerful female monarchs including Elizabeth I (1533-1603); Catherine de’Medici (1519-1589); and Mary, Queen of Scots (1542-1587). In the mid 1580s (just a couple years before the portrait below), Philip Stubbs wrote that apparel is a signifier of biological and social differences between the sexes. I find this somewhat hilarious, given that male clothes had so many feminine features (skirt-like breeches, emphasis on curvy legs, nipped waistline, elaborate embroidery, long hair), and also that King James I of England (1566 – 1625) — who succeeded Queen Elizabeth I — was quite probably homosexual or bisexual and it was known that he bestowed favors upon the male peacocks of the court.

There was a growing acceptance of licentious aristocratic behavior in the 17th century in which the choice of sexual partner was not necessarily restricted to male or female, but could incorporate relationships with boys alongside mistresses without jeopardizing the ideals of “manliness.” The man below has something of the feminine about him with his loose, baggy pantaloons, festive sash, lace garter bows, and pointed toe pose with fist on hip, but this was nothing out of the ordinary for the time:

Male attire was designed to emphasize the soft, curvy lines of the male physique rather than sharp angles at this time — ironically, women wore corsets that virtually flattened their busts. Both sexes wore lace neck ruffs; lace wrist cuffs; coiffed, longish hair; and high waistlines with short pantaloons which emphasized elongated, shapely legs (hoes were often padded to achieve desired visions of muscularity):

King Louis XIV (1638-1715) was aesthetically extravagant in many regards (the Hall of Mirrors in Versailles is testament to that), and clocking in at only 5′ 4″ tall, he undoubtedly assisted the height of men’s shoes: some of his own were 6 inches high! As modern women know, heels also help produce flexed, shapely calves which were still very much in the style of the Sun King’s time. In 1663 the English court adopted the periwig, further feminizing the men of the time (the pointed toe pose should be familiar):

As the century wore on, the periwigs remained, and though men’s legs were increasingly covered, the longer garments that covered them resembled female outerwear, not unlike the unisex Medieval houppelandes, but with modern embellishments like enormous cuffed sleeves:

Post 1700, homosexual behavior was increasingly constructed as a depraved activity associated with a minority of effeminate men; by the 1720s extreme bodily gestures, affected mannerisms in speech and contrived magnificence in costume had come to indicate sexual preference (and perversion). Post-1720, the effeminacy of the previously innocuous “fop” was identified with the effeminacy of the sodomite, adding a significantly more judgmental layer to the language of male attire. The bitter irony is that there was still significant gender crossover in dress. Compare the gentleman below to his female partner: the full skirted frock coat resembles her own skirt; the wide cuffs mimic her lace ones; their gracefully pointed toes meet between them; and the long, coiffed hair is covered for modesty by the woman but styled and flaunted by the man.

The Macaronies of the latter half of the 18th century were often accused of effeminacy, with their outrageously tall powdered wigs, the rosettes on his shoes, and the teeny-tiny three-cornered hat perched atop his sculptural headdress. Macaronies followed the general styles of the time, but typically with tighter silhouettes, often employing vertical stripes to emphasize sleek lines, as in this man’s tights:

Though the wig in and of itself is deliciously ridiculous, remember that Marie Antoinette (175501793) was commissioning equally tall wigs (for women, it’s true):

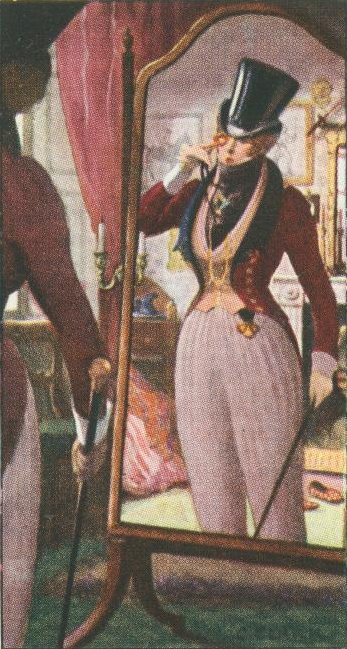

The 1830s brought male girdles that created feminine wide hips and nipped waists (again). Dandy Beau Brummell (1778 – 1840) is credited with creating the modern 3-piece suit with full-length trousers replacing shorter breeches, fitted, tailored clothes, and downplaying flamboyant color in favor of more muted, “masculine” tones. With this feat he also accelerated the separation of male and female fashion crossover. Likewise, the implication of caring about appearance now became associated with the “weaker sex,” whereas in previous centuries men were expected to primp and preen — and for the results to look like they did. Flamboyance was now expressed more subtly in brightly patterned accents like neckwear and waistcoats.

I’m taking a huge leap in time now, assuming that readers are far more familiar with the 19th and early 20th century male fashions and already understand how relatively monochromatic and plain they became after Brummel’s time. With the sexual revolution of the 1960s and Glam Rock of the 1970s, there was a revival in experimentation with sexuality and gender identities. Young men once again wore ornate and ostentatious clothes that often made explicit references to days of yore when the adult population favored the resplendent over the conservative. To wit, Earl Lichfield emulating 18th century male (and yet effeminate with embroidery and ruffles) below:

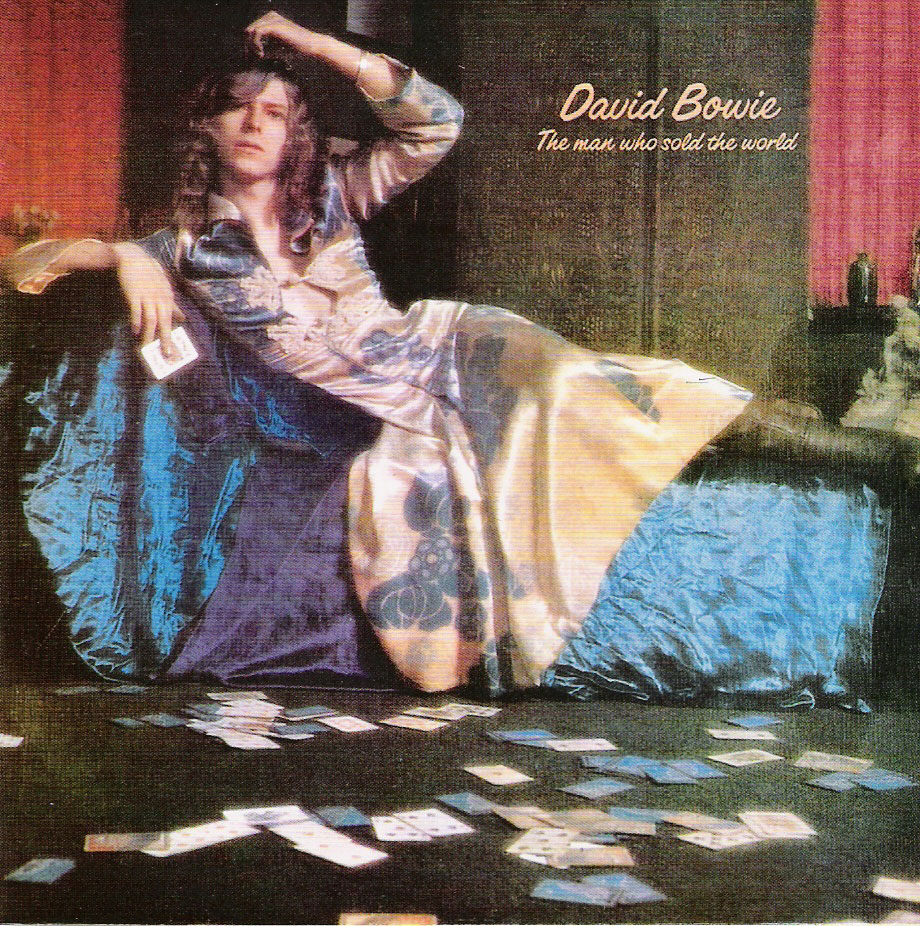

Open bisexual and hugely influential David Bowie (and other glam rockers) deliberately pushed gender boundaries by applying makeup, lengthening hair in deliberately female styles, and wearing high heels. Though the music movement had (and maintains) an impressive following, the gender role-play was viewed by the general public as subversive act of abnormal sexuality.

Allow a detour into Tove’s childhood: at the dentist’s office in the early 1980s, I picked up a small pin of Madonna with ratty, teased bangs, heavy eyeliner and thick eyebrows. I treasured it and wore it on my daily backback. I was absolutely flabbergasted to learn from my best friend (who was a sage 3 years older) that the image was not Madonna at all, but Boy George, a regularly cross-dressing man I hadn’t heard of before!

On the heels of the revolutionary ’70s, the reactionary conservative Regan/Thatcher ’80s gave way to a new generation of cross dressing men, but this was mostlylimited to pop / rock stars like Georgie here, and those associated with the New Romantic music genre including Roxie Music and Adam and the Ants (whose frontman favored an 18th century pirate/aristocrat look with lipgloss and eyeliner):

Current revivals of cross-dressing for men have dwindled again, I’m afraid. Fashion exhibitions like the Met’s “Men in Skirts” (2003-04) confirms that men in skirts are anomalies to be studied behind glass, these days. However, the Utilikilt is a modern-day skirt for the man “man enough” to wear it against gender pressures, with a manifesto including “The Utilikilts Company does not accept preconceived limitations as our own.” Interestingly, it is geared towards men in construction as opposed to gay, fey, or transvestite men, offering comfort, ventilation, cargo pants-like pockets and optional built-in tool belts. Interestingly, it has been adopted by some subcultures like punk and goth kids that are known for experimenting with gender roles in dress:

Um, and also this adorably dorky (but admirably self-possessed) highschooler:

These days fashion remains a female preoccupation in the public’s eye; men supposedly dress for fit and comfort rather than style, and women commonly “make over” their men, keeping gender roles solidly separate in philosophy and image. It’s only been in the last few years that male fashion has swung back to embracing decorative, colorful elements (which the Utilikilt does not). However, I see this as a corporate marketing ploy rather than the ideal acceptance of polymorphous sexuality or the understanding of sexism as dictated by fashion. Marketers simply wanted to capitalize on the largely untapped male market (and the higher income-earners to boot) for what have become “female” products: makeup, accessories, hair products, etc. And thus, the metrosexual was born — a term indicating a heterosexual man who nonetheless adorns himself (like gay men or straight women are supposed to do).

As a final note, gender flexibility in dress has almost always been more acceptable for the elite classes (this was certainly true of the 17th and 18th centuries, and perhaps today as well), where it might be viewed as “eccentric” rather than “deviant.” For middling classes, clear distinctions between feminine and masculine dress signified precious respectability, so they were therefore more reluctant to adopt gender-ambiguous trends. Though I am sickened by the capitalist manipulation it seemingly took to accept a teeny tiny bit of cross-dressing into mainstream fashion culture in the form of the metrosexual, I hope this small step develops further to legitimize gender blurring in dress (because as you can see, we have a strong history of cross-sex trends), and dissolving ideas of “heterosexual normalcy,” and opening the creative channels of personal adornment to all economic strata.

Next week, I’ll dissect female cross-dressing in history, which, though superficially similar in concept, has had different implications of oppression.

7 comments

Histiletto says:

Oct 27, 2016

CROSSDRESSING – a term or its definition would’ve never been used or needed had individuality been able to achieve its stewardship. Each person has their own personality, which generates their tastes and perspectives, whether they are male or female. One’s sex may influence how and what the results of their personality would develop, but so would their social environment, their familial and other relationships, and their religious and secular activities. The whole dynamic of civilization changed when individuality was compromised at the time the control of important personal choices was taken or given to others. The ability to express yourself by what you desired for adorning your appearance was excised or limited to what others of prominent means determined they liked or wanted. Then rules and standards were created to promote this system. The establishment of the gender theory added the munitions needed to set this unnatural process in stone.

So when you go shopping and see something that you want and can afford to adorn your appearance, but society forbids it, remember that it is your natural right to wear that item and society has over extended its jurisdiction and continues to violate your personal agency.

Ellie says:

Jul 7, 2014

This is a brilliant post! I’ve never really understood the whole ‘feminine’ vs ‘male’ thing, as the definitions seem to change every decade or so. I’m a normal straight female, but I very rarely wear makeup, don’t like dresses/skirts, and can’t walk in heels to save my life. A lot of my female friends are the same. So does that disqualify us as women?

Meanwhile, at my uni there are loads of straight guys who wear tight jeans, pink coloured clothes, eyeliner (and more – a lot of the guys wear other ‘products’ rather than ‘make up’, see the difference in marketing?), get manicures/pedicures, and shave their body hair. A lot of women find this look really attractive. I’m one of them. I think men and women are slowly overlapping in terms of gender and it’s just taking a while for the older generations to catch up with this.

Steve says:

Sep 5, 2011

Thank you for this article…

It is so interesting how the majority males have not allowed themselves to think outside the box. But some frown on those who push past this boundary. It’s not right so I understand why many hesitate.

Today, female clothing has incorporated many male items in their clothing choices, like pants. But sadly male clothing has made very little progress with a variety feminine choices, like the skirt. Some males who have ventured down this path are labeled a “crossdresser” and sometimes even gay.

Cross-dressing used to be a complete role reversal not just incorporating a few pieces of clothing. So some see cross-dressing as a sickness, GID, Gender Identity Disorder, and try to cure the person. What are they so afraid of? How can this be “normal”?

I do not need to be cured. I have embraced my masculine side for most of my life suppressing my femininity. I’ve been macho and have followed your “cure”. It’s not healthy nor right to impose this idea of gender on society. I now proudly mix feminine and masculine clothing choices in what I wear. It feels right and I feel more balanced as a person.

Clothing does not dictate my sexual orientation nor should anyone make assumptions or judgements. Everyone should be allowed to wear what makes them happy without ridicule or slander. I am heterosexual for those who might wonder about such things.

Those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it’s mistakes. I think we need to rebalanced ourselves, and our society, with our view of gender, masculine and feminine. Clothing can be that first step and men and women need the freedom to embrace their yin and yang.

crossdressing porn says:

Jun 14, 2010

I’m proud to be a beautiful crossdresser. love this blog

Alaina says:

Mar 21, 2010

One of my favorite subjects. Can’t wait for the female cross-dressing segment!

Georgia says:

Mar 19, 2010

A potent, more recent, and most beloved example of modern, decorative dress for men (as well as your point that upper classes have more flexibility for this sort of thing) is Chuck Bass, the peacock of Gossip Girl. A few examples:

http://bit.ly/dzYAT2

http://bit.ly/caXQIg

http://bit.ly/cqlMgH

It’s important to note that Chuck is a virile, womanizing character, so his dress, which might be seen as effeminate or homosexual, is re-contextualized. He’s become incredibly popular, and in this interview – http://bit.ly/cAdUp3 – the (quite flamboyant, himself) costume designer says that some colleges have been having “Chuck Bass Fridays.”

And, as much as I’d prefer to let it be completely unexamined, it may be worth looking into hipster culture for more study of modern, decorative, and often effeminate clothing for men.

Matt Katz says:

Mar 17, 2010

Great stuff! As always.