In trolling through all the mountains of Fashion Week photos several seasons ago now, I stumbled upon Todd Lynn‘s Spring and Fall ready-to-wear collections for 2011. They caught my attention because, unlike the standard erogenous zones, these focused on the neck — that is, the neck was almost always covered or partially obscured. Stiff collars make heads look like they’re floating, soft furs cuddle faces, asymmetrical flaps of leather strapped to half the neck by way of the armpit (another oft-ignored zone).

I love neck-centric clothes — especially for women’s wear, clothes all too often focus a few inches down, on the breasts. The neck is still highly sensual — soft skin, elongated, smooth lines, one’s throat is rarely touched except by lovers… or aggressors. Because the throat is also highly vulnerable — veins are close to the surface, and essential air is usefully transported from the nose and mouth to the lungs. If these processes are tampered with — via constriction or severing — serious or even fatal damage can be done. But shall I backtrack?

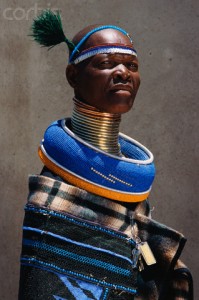

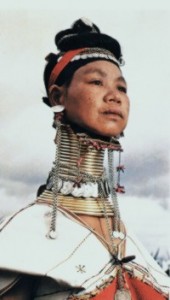

As Harold Koda noted in the Extreme Beauty catalog, an elongated neck implies dignity, poise, and authority across all cultures. It further distinguishes itself as a unique focal point of beauty in that it is not an indicator of youth, as, say, pert breasts and lustrous hair are. Though it is difficult to stretch the neck, drooped shoulders give the illusion of a longer neckline. The Ndebele women of South Africa and the Padaung women of Burma wear heavy coils that weigh down the collarbone, angling it up to 45º (the natural angle is close to 90º); the coils simultaneously stretch the neck vertebrae and slope the shoulders to blur the shoulder line into the neck. These coils also form a protective metal barrier around the weakened throat like armor:

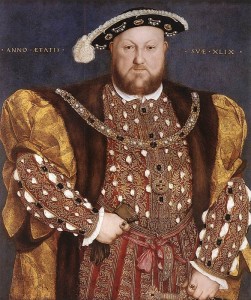

The neck as a focal point in fashion also transgresses genders, as it is equally useful to men as to women as a pedestal on which to drape symbols of wealth, authority and beauty. Historically, bishops and kings have been just as likely to adorn their necks as women. Note the triangulated silhouette of the Cardinal’s cape, obscuring his shoulders and drawing the eyes to the apex, his neck and head; the heavy medals and necklaces advertise these men’s wealth and authority:

Though in daily life necks are covered by soft material, 16th century menswear was influenced by armor design –Â a sign of masculine strength and virility — which subtly implies the vulnerability of the neck and the necessity of covering it. In the pictures below you can see how armor and soft cloth mimicked each other in skirt, faux pleats, squared-off toes, etc. Though Henry’s neck is not protected by metal, in both portraits (above and below) he clutches a glove and a dagger, indicative of duels and violence:

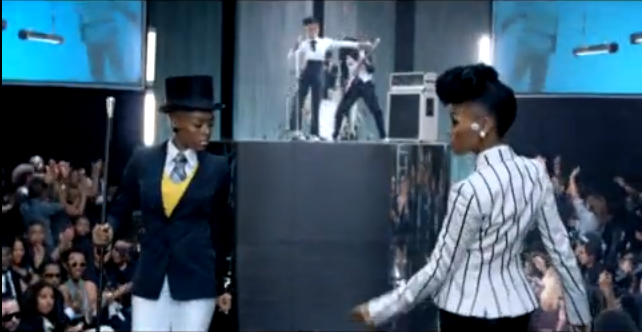

John Galliano employed both the triangulated shoulder illusion of male robes, and the extending Afro-Asian neck coils in his otherwise European-tailored suit and choker for Dior‘s FW97 collection. Todd Lynn conceived a more pared-down, monk-like version for his coat that obscures and therefore highlights the neck:

From the 16th through 19th centuries, corsets were constructed with shoulder straps that similarly triangulated a woman’s shoulders. Rather than extending the clothes from shoulder to chin, clothes were cut away from that area, exposing the flesh of throat, upper back, and shoulder top to lengthen that same line. These necklines perhaps don’t scream “danger!” at first, but the fashionably exposed necks certainly contribute to the pervading sense of unease viewers experience while watching Dracula films, am I right?

Just post-French Revolution, a small but highly visible group of radical dandies — the Incroyables — took to winding neck scarves up the length of their necks and even over their chins; it has been speculated that this was a symbolic protective measure of that part of the body that had recently been targeted by the dreaded guillotine. Compare to the structured high collar in Todd Lynn’s collection that captures some of the aggression and unease present in the turn-of-the-19th century example:

Vampires and slashers share a similar modus operandi: both are sexual, aggressive, and violent, usually focusing on or around the neck which, as I hope I’ve already conveyed, embodies sensual vulnerability. The collar from Alexander McQueen‘s “Dante” collection (FW97) is protective in its height, but aggressive in its angularity; its plunging slashed neckline is further exaggerated by the dramatic upward sweep of the starched-like collar. Similarly, Todd Lynn’s blood-red ensemble covers the neck, shoulders, and chin, but exposes a slice of flesh just below:

All this to say, I’m ready for more neck-centric fashions. Who’s with me???!!

!['Yume' Day Bed [Walnut] — Konk - Custom Handmade Furniture](https://i.pinimg.com/236x/e7/84/be/e784bebeb3ca0d2d641a84d05263c436.jpg)

![Kobi Drawers [Walnut] — Konk - Custom Handmade Furniture](https://i.pinimg.com/236x/2a/94/9c/2a949cb1b94b72fd45d6a1dba4f8f5cc.jpg)

4 comments

kit kat says:

May 2, 2013

dickeys are returning to the runway as well!!

Bethany says:

Feb 9, 2013

I’m so glad to have happened upon this post! I’m exploring the idea of the human neck as an object of vulnerability and sensuality in an art series…this is so interesting and very helpful!

Victoria says:

Nov 14, 2012

Like the idea of sensualising the neck but real fur just reminds me of the inherent cruelty of the Chinese fur farms, as stuffy and pompous as it was on Henry VIII but with even more common brutality, makes women look older

Selah says:

Oct 7, 2011

Really liked this post! I share the love of neckcentric fashion, and my winter coat has a collar that covers half my face. I’m glad I’m blessed with a long neck!