With all the excitement of the Kentucky Derby culminating last weekend, I thought I’d take the opportunity to learn about (and share) the roots of horse racing apparel. To begin with the basics, jockey “silks†are comprised of white breeches and a bib, stock or cravat, and receiving them is a rite of passage for jockeys entering their first race ride. Horsemen wearing “colors” (as they’re also known) has a long, illustrious past that has developed with the various horse sports. In ancient Rome for example, chariot drivers wore unique, brightly colored capes and headbands to identify themselves in the arenas. Roots in heraldry and coats of arms can be seen, the decorated shields and armor of which identified members of families and soldiers on battlefields, as jockeys came to be identified by their silks:

This is a German Hyghalmen Roll with coats of arms, circa 1485. Note the simple shapes and limited palette.

Horse racing meets are recorded as far back as 1114, and individual silk colors are first mentioned in 1515 when Henry VIII occupied the English throne. In those early days of horse racing, few horses would compete and close finishes were rare enough that identification was not terribly problematic, but in the 18th century, racing gained popularity. As more horses competed in each race, riders wore simple colored silk jackets to combat increasingly confused judges and spectators. This was not an entirely new idea: in medieval times, jousting knights wore bright, distinct colors which facilitated the identification of the competitors for the audience members of large arenas:

In 1762 the English Jockey Club formalized what had been a general practice and requested that owners submit specific colors for riders’ jackets and caps, which were to be used consistently. Later that year they made the Newmarket resolution that owners must submit the racing silks for their horses to compete. From the minutes: “For the greater convenience of distinguishing the horses in running, and also for the prevention of disputes arising from not knowing the colors of each rider, the under-mentioned gentleman have come to the resolution and agreement of having the colors annexed to their names, worn by their respective riders.â€

More rules have been implemented since then. The horse owner or trainer selects and registers their jockey’s colors (which includes colors and patterns) in national horse races; typically all horses belonging to a particular owner will be raced in the same colors. The owner must check the appropriate database (Weatherbys for England, The Jockey Club for the United States, Puerto Rico and Canada, etc.) as each racing silk must be unique. Patterns are created with squares, lines, circles and stars of contrasting colors. Uniforms at national races are very bright but regulations dictate a maximum of 4 colors. Japanese rules mandate that the hat color must match the gate color, but in other countries it must match the uniform.

This looks similar to the racing cheat-sheet I was given at the Irish tracks, which listed the horse names, jockeys, and had a crude depiction of the colors. You can see that Don’t Get Mad and Greeley’s Galaxy are owned by the same person.

Jockey silks used to be made of actual silk, though it is unsurprising that synthetics like nylon are often used nowadays, as they are for other athletic ensembles. The cut of jockey silks is close fitting for minimal wind resistance — important when tenths of seconds can make the difference between first and second places — but not tight, as the rider must have freedom of movement. Thin, lightweight materials like silk are ideal for ease of movement, breathability, and not adding bulk to jockeys for whom low weight is a necessity. Long or short sleeves may be chosen but jockeys usually prefer long sleeves that minimize chafing. A 2005 lawsuit granted The Jockey Club the right to add small logos and advertisements to the jockey pants which had previously been pure white. It’s interesting to me that this sport previously resisted the seductive pull of ostentatious corporate sponsor logos that have visually taken over another track sport: car racing.

It behooves (ha!) jockeys to stand out from others not only to distinguish themselves from their competitors, but also as walking (or running) advertisements for the owners, the jockeys’ employers (even without literal sartorial branding). In a time when casual attire is more and more the norm, on the horse tracks pride in performance is still displayed with bright, shiny, colorful and patterned silks, where historically the attendees have been the upper class bourgeois, dressed in their own finery to see and be seen. This leads me into the class struggle that I see on the horse tracks.

I believe the jockey silks serve yet another purpose: to distinguish them — the hired talent — from the owners and spectators. The owner-dictated colors to be worn by jockeys are already a kind of stamp of claim, and professional jockeys — unlike gentlemen who ride or hunt for leisure — are typically culled from the working class who often got their starts as humble stable boys. In his fascinating book “City Games: The Evolution of Americann Urban Society and the Rise of Sports (Sport and Society),” Steven A. Riess notes that “thoroughbred racing and yachting, strongly identified in the public mind as elite sports because of the exorbitant cost of participation and the restricted memberships of jockey and yacht clubs, served as status-defining communities.” After being banned during the American Revolutionary era because of its associations both with the unpopular elite and immoral gambling, Jockey clubs were eventually created and justified “as the only means of developing superior horses for such uses as national defense (the cavalry) and transportation.”

Here is a card (c. 1876-90) depicting children dressed up as various professionals. Note that the jockey is included in an all-working-class / subservant lineup with coachman, concierge, and maid.

The horse track is one of the few daytime, outdoor activities where formal attire is expected; it’s the plein air version of a night at the opera where the rich and famous (who may or may not actually care about the race outcome) can “see and be seen” while peering through their binoculars as opera-goers peered through their opera glasses. Mint juleps are served to daintily sipping guests while mud and dust spattered horses and jockeys are running for their lives — and sometimes to their deaths. These jockeys, though respected after wins, have been depicted in rather startling ways.

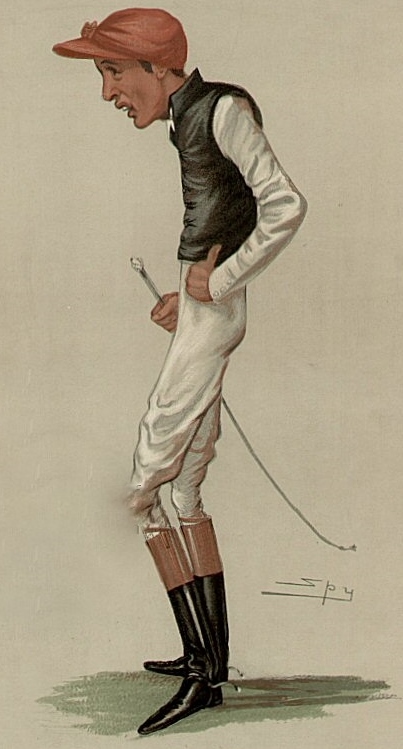

Jockeys are often portrayed as either boyish and/or with hunched posture:

This begs physical comparison with jockeys’ equine partners, as The Triplets of Bellville (2003) portrayed their cyclist athlete as a kind of horse-slave:

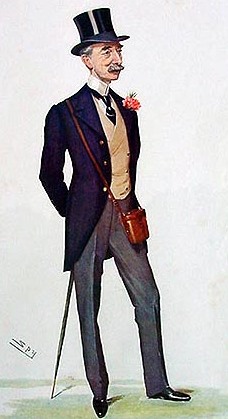

Compare to a horse owner. Note the erect posture, with top hat to emphasize his stature physically and socially (men of lower classes wore different hat styles):

The wonderful scene in My Fair Lady (filmed in 1964 but taking place circa 1916) illustrates the class prerequisite of the races. Lower-class Eliza Doolittle has never attended the races before, and her behavior in the exclusively upper crust setting is the final test of Henry Higgins’ skill, who has forced himself upon her as her aristocratic mentor. It also displays Cecil Beaton’s interpretation of the conspicuous fashion that lives on even today, with great humor and only slight exaggeration:

A marvelous irony is that horse racing was one of the first venues for legal gambling (it has been argued that its popularity continued because of this), so for every preening attendee there is a gambler who probably cares less what he looks like or where he sees or hears about the race and more who actually wins, (wearing whatever he damn well feels like).

Though I am undeniably attracted to race horsing as a genteel, civilized activity (I could never say I don’t love excuses to wear big hats, for example), my pragmatic, socially progressive side abhors the class distinctions that the races perpetuate, exemplified still in the attire of athletes, attendees, and remote observers.

2 comments

jerry says:

Jun 13, 2012

Excellent web page on history of jockey racing silks, though having a bit of a problem finding silks for Hamburg Place in Lexington, Kentucky

parisbreakfast says:

Dec 29, 2009

MJ looking very smart in a jockey outfit, whilst his brothers are in race car getups..

http://i.usatoday.net/life/gallery/2009/l091116_opus/jockey.jpg