I happened to run across an old issue of Hue, FIT’s alumni magazine, and read a surprisingly interesting article on “The Life and Times of Mannequins” by Alex Joseph. Though I have not previously studied dress forms in depth, I have been mistaken for a mannequin (I spaced out in a flu-induced frozen position while waiting for a friend when another customer hilariously reached out to inspect my garment), and I’m also drawn to the creepiness I think is inherent in mannequins… and so I’ll pretend my recent reading list and newfound interest qualifies me to inform you about the history of stationary models.

The Dutch word manneken literally means “little man,” though most mannequins were and are technically female forms. As the history of dress dates to ancient times, so does the history of dress forms; a wooden torso was found near a clothing chest in King Tut’s tomb, dating to approximately 1350B.C.:

Thousands of years later, European monarchs produced “fashion dolls” as examples of national style — Charles IV of France sent one to Richard II of England in 1396 as part of a peace negotiations. And Henry IV of France (1553 – 1610) dispatched miniature, elegantly attired dolls to his fiancée, Marie de’ Medici of Florence. Caroline Weber goes into amazing detail about the deliberate Frenchification of Austria-born Marie Antoinette in her book, similarly to update her on French trends and therefore facilitate her connection to her stylish adopted land and people. Monarch aside, these miniature models were used to spread the latest trends across countries throughout the 1700s. But it would take technological advancements to move the dress form from private doll to public display item.

The mid-19th century inventions of electricity-fueled incandescent light bulbs and plate glass enabled merchants to create window displays to advertise their goods. Add the ease and speed of manufacturing ready-to-wear clothes afforded by the invention of the sewing machine, and it becomes obvious why the mannequin became a standard display prop at this time, surpassing its initial dressmaker’s functionality. The department store established itself in the American way of life by 1910, and these larger businesses had more money to invest in expensive mannequins which would ideally help them move the quantities of merchandise they needed to. Facial expression and body language became increasingly important (ancient and pre-Victorian forms were often headless) as window dressers like L. Frank Baum (known for his masterpiece The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, 1900) used them to create arresting vignettes on their mini stages. “Window gazing” became a popular pastime for potential customers, eventually morphing into the familiar “window shopping.” Dressmaker suppliers like Gems Wax Models (est. 1885) and Siegel and Stockman of Paris experimented with articulated legs, arms and wooden hands with bendable digits in an effort to more closely mimic human activities, if stiffly. The latter company even began to produce sitting figures, bicyclists and representations of celebrated athletes at the end of the 19th century (see my post on Bicycles and Athletic Fashion). Sometimes with glass eyes, realistic teeth and human hair, attempts to make early mannequins more lifelike ultimately resulted in creepiness. Iron feet stabilized their teetering skeletons but contributed to unwieldy heft — they could weigh up to 300 pounds.

Skin-mimicking wax had the downside of melting under hot electric lights and cracking in cold winters. Subsequent mannequins constructed of plastic and papier mâché were more durable, lightweight, and flexible, making them easier to imbue with lifelike gestures.

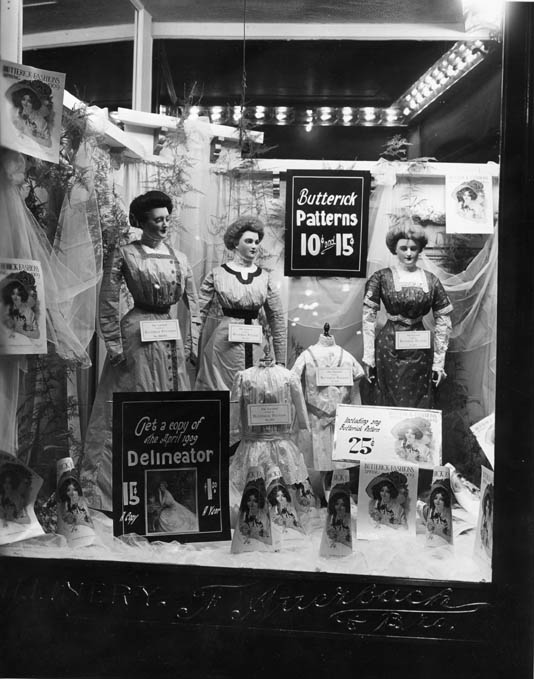

Compare this 1909 storefront…

to one from 10 years later. Note the increased interaction between mannequins, the more sophisticated, narrative scene:

The 1929 stock market crash garnered invention in many ways. In the teens and early 1920s mannequin facial expressions became more animated, perhaps a reaction to silent films. Khol-rimmed eyes, bee-stung lips and razor-thin eyebrows that gained acceptance and popularity on the silver screen were transcribed onto new mannequins. Made with papier-mâché, the new material shed off about 100 pounds, coincidentally embracing the more slender female form, often with Mannerist-like elongated necks:

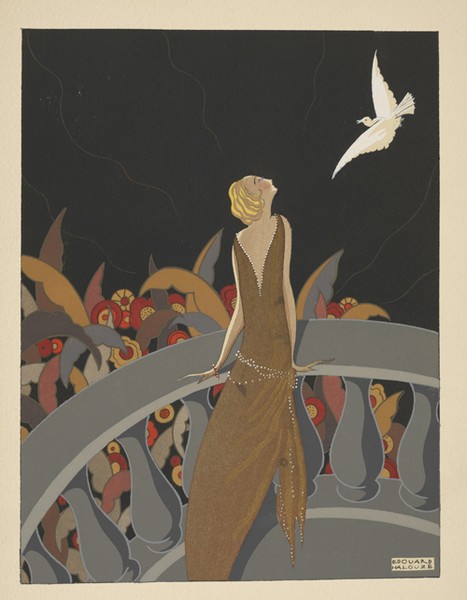

In 1925, Siegel & Stockman, Paris startled the display industry with abstract mannequins in 1925 that mimicked the clean lines of Art Deco. Siegel himself said “The old mannequin, too realistic to respond to the abstract form assumed the architecture and decoration, could no longer fit into the window display with its effective and sober luxury as it is now conceived. This basic conviction prompted me to make an appeal to a new form of expression in order to bring about a timely rejuvenation and modernization.”

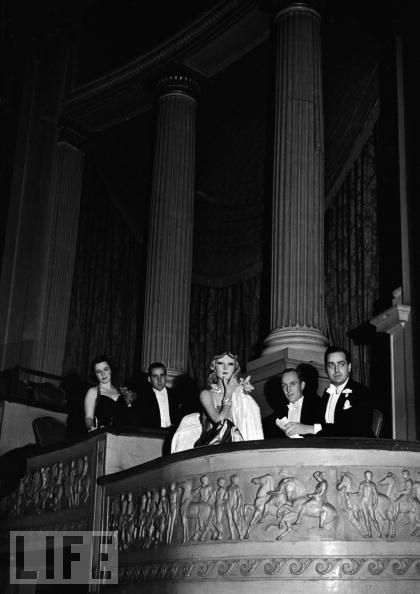

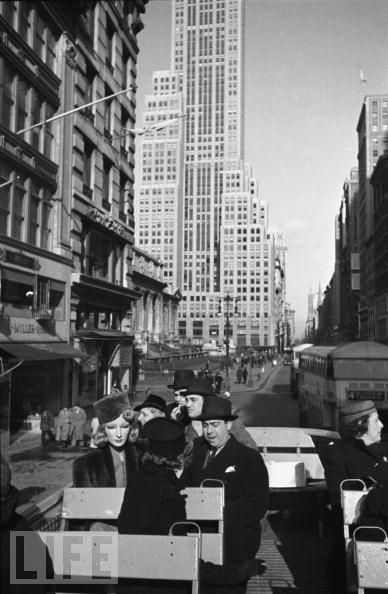

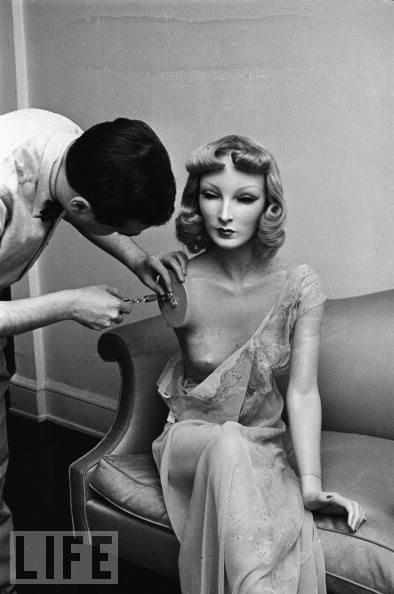

Author Nicole Parrot observed the “elegant and snooty” look of the 1920s were replaced with the “pert and gamine” look in mannequins during the Depression of the 1930s. An Austrian dollmaker-turned-mannequin manufacturer, Kathe Kruse, devised a metal skeleton that was covered with a skin-like material, enabling a variety of positions. “Cynthia” was a 100-pound model created by Lester Gaba in 1932 who had realistic imperfections like freckles, pigeon toes, and even different sized feet. Gaba posed with Cynthia around New York City for a Life Magazine shoot that humorously demonstrates how lifelike the mannequins had become:

Tragically, Cynthia met her demise when she slipped from a chair in a beauty salon.

The more severe mannequin expressions reflected the unease and hardships of WWII. As a fashion historian I already knew that the dress silhouette in the 1940s became slimmer and less embellished to waste less fabric, due to raw material shortages and wartime rationing. I only recently learned, however, that mannequins themselves were made to be shorter than the 1930s models, with the same goal of conserving precious resources for the war effort. At the war’s conclusion, Mayorga Mannequins introduced “Welcome Home Mannequins” where a man and woman held their hands outstretched towards each other, while a small girl looked expectantly at her father. This narrative was tempered by glamorized Hollywood poses that were also available, but traditional family values (including consumerism) continued to be recreated in storefront vignettes:

This article will be continued shortly in Part II…

5 comments

Anthony Navarro says:

Jun 3, 2018

Hello Mr. Hermanson,

I have Paintings and art work that you might find interesting as a fashon historian related to an article the politics of mannequins you wrote. Specifically Gabriel H. Mayorga former creator of Mannequins of Mayorga.

I can be reached at the above E-mail I hope to hear from you soon.

Thank you Anthony Navarro

Marsha Bentley Hale says:

Feb 9, 2012

It is great to see your writings regarding the mannequin. I have been researching the history of the mannequin since 1978. I am not certain if my early articles are still available on line. “Body Attitudes” 1983 (Visual Merchandising and Store Design), “Lasting Expressions” (VMSD) 1985, and “Future Mannequins Past & Present Tense” (Retail Attraction) 1986? I wrote articles for five years for FashionWindows.com. If you would like me to send copies of my aritcles I would be happy to. I am giving a lecture at The University of Chicago of February 12, 2012. My archives are extensive. My research regarding mannequins has been on the back burner while I worked on my PhD (Chick Flicks and Weepies The Mythology of Love in Film). Marsha Bentley Hale

Jean says:

Jun 22, 2013

Hello,

I’ve tried to search some of your articles regarding mannequins but unfortunately I couldn’t find them online. I would be extremely thankful if I could take a look at them. I’m also very interested in history and trending of mannequins. I came across your name and interest in the same topic in one article which includes very detailed and elaborate research on mannequins. This is the link to the article: http://mannequinmadness.wordpress.com/the-history-of-mannequin/

Looking forward for your response.

Jean

Hillel Schwartz says:

Jul 12, 2013

I was trying to get in touch with you for years while writing my book,

The Culture of the Copy: Striking Likenesses, Unreasonable Facsimiles,

which appeared in 1996 with a sizeable section on the history of mannequins. I would like to cite your work in the re-edition of this book scheduled for late this year. Please get in touch with me.

Hillel Schwartz

Olivia Gecseg says:

Mar 18, 2016

Dear Marsha,

I am a student at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London and I am writing a historiographical essay on the history of the mannequin. No essay would be complete without your work, but I cannot find your articles anywhere! Please get in touch with me, I would be ever so grateful. My email is ogecseg@gmail.com. Thank you